Reading Notes: Autograph

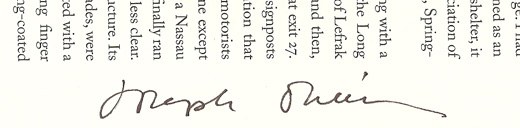

Joseph O’Neill, author of Netherland, read from his novel and signed copies at the 82nd Street branch of Barnes & Noble this evening. I bought the novel for the fifth and sixth times. The first copy, you can read about here. The second copy, purchased at St Mark’s Bookshop, went to the other O’Neills, my daughter and son-in-law. The third copy went to Lady Diana (our Lady Diana, sister of late House Secretary Sir Kenneth Bradshaw). The fourth copy is destined for Nom de Plume. I don’t know what I’ll do with the fifth copy, but don’t worry: the one sure thing is that I’m not giving away the sixth copy that, very obligingly, Mr O’Neill signed for me on page 135, alongside the following passage:

There we instantly became confused by a succession of signposts placed in accordance with a bizarre New York convention that struck me again and again, namely, that all directions to motorists should be so located and termed as to disorient everyone except the traveler who already knows his way.

With this single sentence, Mr O’Neill proves himself to be the master of New York life that Tom Wolfe so entertainingly but regrettably showed himself not to be when he built an entire novel on a “save” that, while it might work anywhere else in the country, no born and bred New Yorker (“Sherman McCoy”?) would think of trying. As a traveler who grew up on local roads, I had the leisure to note how useless the signs were. If you’re on the Bronx leg of the Triboro bridge, hoping to get closer to Times Square, and you suddenly see the “Downtown NYC” sign with its little arrow, you’re probably toast. Your chance to position yourself in the correct lane expired fifty yards ago.

And then there’s the beautiful prose in which Mr O’Neill embeds his observation.

So, bibliomanes everywhere: know that there is a copy of the most beautiful novel in the world that does not, on its title page, appear to be a “signed” copy. Whilst, one fine day many centuries from now, in a world that, it’s to be hoped, has not been reduced to cinders (I’m not giving up the book any sooner), a general reader will turn the page and frown, seeing what you see above. What’s, she will ask, that about?Â