Monday Morning Read

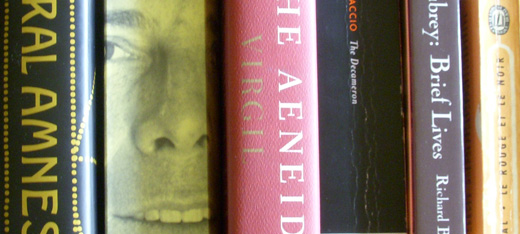

¶ In the Decameron, more rather unsophisticated humor. Rushing off to scold the beautiful nun who has been caught with a handsome young man in her room, the abbess gropes in the dark for her veils but instead dons the breeches of the priest who is visiting her. Now, I’d like to see that get past the censors in today’s Hollywood — and don’t think that there aren’t any!

¶ In the Aeneid, a fury to be done with this epic lashes me as mercilessly as Camilla, decus Italiae virgo, whips her charger, so I read all the way to the end of Book XI. Plenty of Iliad-ic gore, with a dash of divine intervention.

When I was young, and busily avoiding the study of Latin, I nevertheless thought that the Aeneid stood at the pinnacle of Roman brilliance, and that, therefore, it marked some kind of advance — over what, I had no idea. But now that I am old, and know a thing or two about Virgil’s patron, Augustus (“the Widmerpool of the ancient world,” according to A N Wilson), the Aeneid seems both unbeautiful and retrograde. It’s of some use to anyone who likes paintings, because its scenes have provided so much fodder for patron-pleasing artists; and, here and there, I find the taut beauty that I expect of Latin, which remains a language that I have not mastered. On the whole, though, I’ll simply be relieved to stop claiming that there’s no need to read a book that I happen not to have read — always an uneasy position — and to start claiming that there’s no reason to read a book that I have, even if my opinion oughtn’t to count for much.

¶ In Aubrey, the life of Robert Hooke, a leading figure of the Scientific Revolution, much admired by Aubrey. Here’s a bit of armchair psychology that I would contest, however:

Now when I have said that his inventive faculty is so great, you cannot imagine his memory to be excellent, for they are like two buckets, as one goes up, the other goes down.

It’s more interesting that. Inventiveness, like poetic skill, comes not from lack of memory, but from a very certain kind of faultiness in the memory that permits its lucky victim to remember something that, although it wasn’t quite there to remember, proves to be new and useful. As such, it is no more “faulty” than the mold that turns milk into Roquefort. I would call it an excellence of memory. What Aubrey has in mind seems adequately handled by my laptop.

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, Julien paces in his cells (in Verrrières and Besançon), thinking heroic thoughts of triumph, remorse, tenderness and despair. It would all be so much better if sung to Berlioz.

¶ Clive James on Coco Chanel: a tightly compressed, almost constipated piece. You expect James to lacerate Chanel for her wartime accommodations of the Nazi regime, from which she was lucky to escape, thanks to the existence and hospitality of Switzerland, with her head unshaved, but instead he goes off on the crime of Soviet Communism against the Russian people — and, once again, the designer keeps her hair as well as her head.

Soviet consumer good were an insult. They were already rubbish when they were fresh from the factory, and the fate of the people who had slaved, saved and stood in endless lines to buy them was to find that they could not even be cherished, because they were already falling apart. Meanwhile, the tastes of the ruling elite gave the game away. No Soviet diplomat based abroad ever returned to his homeland without a few bottles of Chanel Nº 5. So Coco Chanel, who had rolled over for the Nazis, played her part in discomfiting the next dictatorship to come along.