Friday Morning Read

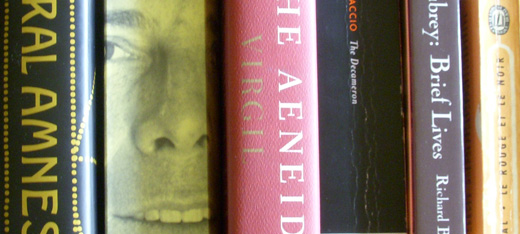

¶ The Ninth Day of the Decameron begins with a Laurel-and-Hardy prototype, as two Florentines, unknown to one another, are charged with a very unpleasant task by the lady from Pistoia whom they both admire but who wishes to be rid of their “importunities.” If the story is not Boccaccio’s most successful, that is because its blend of comedy and Gothic horror no longer emulsifies. It’s not that we can’t have fun with dead bodies anymore — just think what Boccaccio might have done with the recent tale of Virgilio Cintron. But, perhaps because romantic comedy has come to be our foremost celebration of life, we find the odor of death unpleasantly incongruous. By our lights, the lady from Pistoia’s plot is in very poor taste.

¶ In the Aeneid, translator Robert Fagles has Turnus cry out, “Bring him on!” (meaning Aeneas), but I can find nothing in Virgil that supports this now-debased invocation.

¶ In Aubrey: Holder, Holland (Hugh), Holland (Philemon), and Hollar. Of William Holder’s wife — who happened to be Christopher Wren’s sister — Aubrey notes not only that she was an excellent “she-surgeon” but, what impresses him more, also that “which is rare to be found in a woman) her excellencies do not inflate her.” A text for Germaine Greer to gloss.

¶ The staggering climax of Chapter 35 of Le rouge et le noir beats everything for precipitate event. Julien dashes off to Verrières, equips himself with pistols, and shoots Mme de Rênal at Mass! In evident response to the marquis’s inquiries (of which we’ve heard nothing until now, for all that we have heard about the marquis’s thinkings), Mme de Rênal has written something of a poison-pen letter, assassinating Julien’s character. So he has only one and a half or two pages in which to enjoy his new lieutenancy and his fine uniforms. So much for the red!

Le rouge et le noir is the novel par excellence for bright, disaffected adolescents, whose passions and hormones rage too violently for them to mind the novel’s carelessly flimsy construction.

¶ Writing about the aphorist Chamfort (1741-1794), Clive James issues two pearls, one in his preface and one in the original piece. From the preface:

The Revolution had given birth to ideological malice in a form we can now recognizde, but it was not recognizable then. It was still discovering itself. Chamfort, by the time that he ran out of luck, had already defined some of its characteristics, but not even he had guessed that it couldn’t take a joke.

And from the piece:

Evidently Chamfort helped de Gaulle to believe himself a bit of a devil. It is possibly the secret of the attractive wastrel, as a type, that reasonable men see in him the road not taken: his seemingly effortless charm allays momentarily the consideration that for them the road might never have been open.