Thursday Morning Read

In the current issue of Bookforum, Paris Review managing editor Radhika Jones interviews writer and editor Daniel Menaker in his Upper West Side apartment, where she makes the following observation about his library.

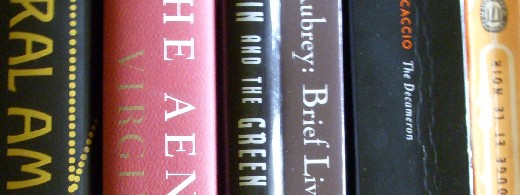

The fiction that remains—a largely canonical selection—is shelved alphabetically by author or subject, from Aubrey’s Brief Lives to Zola: A Life.

I am sure that this is a slip, that Ms Jones meant to say “literature,” not “fiction.” But still!

¶ In the Decameron, VI, vii, the famous story of Madonna Filippa, who confronted her judge, upon being charged with adultery and facing the local penalty (the stake), with the complaint that the relevant law was a bad law because it had been promulgated without consulting women. This, of course, isn’t the argument that gets her off. What gets her off is the court’s inability to tell what to do with “the surplus” that’s left over after she has given her husband all the loving that he requires. “Surplus” is McWilliam’s word. Boccaccio is finer and deadlier.

“Adunque,” sequì prestamente la donna, “domando io voi, messer podestà , se egli ha sempre di me preso quello che gli é bisognato e piaciuto, io che doveva fare o debbo di quel che gli avanza?

“Well then,” the lady went on quickly, “I ask you this, your honor: if [my husband] has always taken from me what he needs and wants [in the sex department], what was I — what am I supposed to do with that which exceeds it?

Is she to throw it to the dogs? Let it rot? Note that the metaphors for frustration are couched in the language of food and spoilage. It would take the Industrial Revolution to teach us to talk of our carnal and other passions in terms of hydraulics (exploding boilers &c).

¶ In the Aeneid, Virgil closes Book VIII with a description of the shield of Aeneas that glosses quickly over the highlights of ancient Roman history — all foreseen by Vulgan when he forged and wrought the armament — before lingering lovingly on the Battle of Actium (at which Octavian, who would become Augustus, Virgil’s greatest patron, defeated Antony), with an emphasis on the despair of “nefas” Cleopatra.Â

¶ John Aubrey, the “author” of Brief Lives, would have rounded out the preceding paragraph by appending at note to “enquire” about Auden’s poem, “The Shield of Achilles.” Brief Lives has come down to us very much as a work in progress, perhaps the work in progress par excellence.

I was too worn out, this morning, by the long and very miscellaneous entry for the author’s great-grandfather, William, to dig into the even longer biography of Francis Bacon the Earlier. Near the end, Aubrey shrugs and sighs:

The curse of heroes’ sons: he used up all the wit of the family, so that none descended from him can pretend to have any.

The which does suggest that Luck has a Lot to Do With It.

¶ In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, I find myself turning with mild dissatisfaction from what strikes me as implausible translation for reassurance by the original. Consider:

Fastened in his armor he seemed fabulous, famous,

ever link looking golden to the very last loop.

That’s Gawain, setting forth on his quest for ordeal. If there was ever a word that seemed out of place in this very manly, Middle-English context, it’s “fabulous.” All the awareness in the world of its original denotation (“of or pertaining to a fable”) fails to render it apt. Here’s the original:

When he was hasped in armes, his harnays was ryche;

The lest lachet other loupe lemed of golde.

Equally unfortunate is the following passage. Gawain has gained entry to the grand castle and is getting ready for dinner.

He chose, and changed,

and as soon as he stood in that stunning gown

with its flowing skirts which suited his shape

it almost appeared to the persons present

that spring, with its spectrum of colors, had sprung;

so alive and lean were that young man’s limbs

The idea is certainly there in the original, but the tone seems off. The translator of any non-contemporary text faces the challenge of meeting deeply incompatible challenges. Do you translate the excitement into completely modern terms — thus occluding the peculiarities of the original? Or do you try to import the strangeness of the past into the translation, with a view to widening the reader’s perspective? On the whole, Simon Armitage’s translation reconciles these objectives, but these apparel notes do not.

¶ Chapter XIII of the second part of Le rouge et le noir is entitled “Un Complot” (“A Plot”), but this plot turns out to be the product of Julien’s fevered imagination: he’s obsessed with the possibility that Mathilde is plotting to humiliate him by tempting him, as Tartuffe was tempted, into thinking that she loves him, even though he is only a “carpenter’s son” (interesting echo, there). Trying to outfox Mathilde is like a love-potion.

Il excitait son imagination plus qu’il n’était entraîné par son amour.

He was working his own imagination up rather than being carried away by love.

¶ Clives James on Miguel de Unamuno — but not really. After a brief biographical sketch, the essay proper falls into two parts. The first roams freely over several topics but seems anchored in books; James’s bibliophilia has finally begun to register with me. (On marking up books by Unamuno: “One hesitates, because his books are usually very pretty physically. Invariably published by Aguillar, his early collected editions on thin paper are hard to find now. I found most of mine in two very different….”). The second, even briefer, ends with this somewhat gnomic syllogism.

The best writers contain within their souls all the characters they will ever create on the page; and those characters have always been there throughout history; so the writer, no matter how modern he thinks he is, deals always and only in certainty.