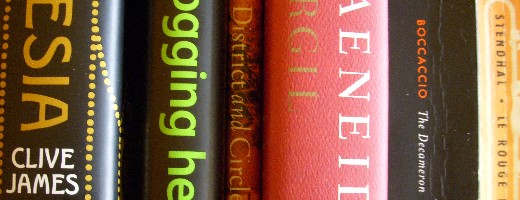

Tuesday Morning Read

¶ The Decameron, VI, ii: No wonder the “tales” are short Today (on Day Six, that is): they’re really just set-ups for snappy comebacks. To have two G-rated stories in a row is also a novelty.

Today’s riposte concerns a prosperous baker, a very fine white wine and a greedy servant. When a diplomat’s servant shows up at the bakery with an outsize flask, the baker playfully insists that he has come to the wrong address? Where was the servant meant to go? Well, with a flask that large, to the banks of the Arno. The diplomat scolds the servant for having tried to impose on the baker’s generosity.

The bit about how the baker catches the diplomat’s attention in the first place is worth reading. Boccaccio’s imagination has the most interest way of flitting between the Arcadian never-land of old romances and the rigorously class-conscious world in which he lived.

¶ In the Aeneid, the story of Hercules and Cacus. According to the Oxford Classical Dictionary (2003), this “provided an aetiology for the cult of Heracles at the Ara Maxima.” In other words, one of Virgil’s numerous just-so stories. You had to be Roman…

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, a rather wonderful chapter that, for no good reason, brings Ian McEwan’s Atonement to mind. Maybe it’s just that it’s so easy to see Keira Knightley playing Mathilde de La Mole, a beautiful young aristocrat whose intelligent but naive egotism leads her to admire a visiting Spanish nobleman (little could Stendhal anticipate what this character’s title, Count of Altamira, would mean to later readers, at least after 1879) simply because he is under sentence of death back at home in Spain. Mathilde dangerously — dangerously for Julien, one can already feel — concludes that a death sentence is the only grand thing that can’t be bought and sold in today’s rotten world.

Qu’est-ce qu’un méchant pourrait objecter à mon bon mot? se dit Mathilde. Je répondrais au critique: Un titre de baron, de vicomte, cela s’achète; une croix cela se donne; mon frère vient de l’avoir, qu’a-t-il fait? un grade cela s’obtient. Dix ans de garnison, ou un parent ministre de la guerre, et l’on est chef d’escadron comme Norbert. Une grande fortune!… c’est encore ce qu’il y a de plus difficile et par conséquent de plus méritoire. Voilà qui est drôle! c’est le contraire de tout ce que disent les livres… Eh bien! pour la fortune, on épouse la fille de M Rothschild.

Réellement mon mot a de la profondeur.

The problem, as Stendhal so beautifully catches it, is that the young lady is talking to herself. Her “bon mot” has occurred to her as she surveys the scene at a ball, and not, as would be vastly preferable, in the course of a conversation among clever people. We’re assured that “Mathilde avait trop de goût pour amener dans la conversation un bon mot fait d’avance.” But, the sentence continues, “mais elle avait aussi trop de vanité pour ne pas être enchantée d’elle même.” But because she cannot discharge her burst of wit in a verbal sally, it abscesses toxically.

Maybe I just like ball scenes, but this is the first chapter of Le rouge et le noir to make me feel that the book is truly indispensable.

¶ One did not expect to encounter Margaret Thatcher in the pages of Clive James’s Cultural Amnesia, but her presence turns out to be extremely apt. Although as an opening thrust James makes fun of her solecism, Solzhenitskin, and follows this up by both patting himself on the back for being the only commentator to catch the conflation of the Russian sage and the dwarf from Grimm, and laughing at himself for having confused Rumpelstiltskin with Rip van Winkle (“making cheap cracks about Thatcher’s having suggested that Solzhenitsyn had been asleep for a hundred years”), the piece is a timely warning against the danger of allowing intellectuals to meddle in politics.

In the long run, Thatcher’s mistake, whose consequences we have all inherited, was to listen to her intellectuals not only on the level of slogans and smart remarks but on the level of their convictions. Her own fundamental notions would have seen her through. Her electoral base, for example, expanded into the working class as a natural result of her inbred conviction that people would look after council houses better if they were given the chance to buy them. With her widely admired passion for good housekeeping, she could have opened Britain to the free market without dismantling its civilized institutions, and so won kudos all round. The institutions had their representatives in her cabinet, but it turned out that they might as well have been speaking from the Moon. Her free market ideologists, on the other hand, could approach her in private, where they had access to her ear as her cabinet colleagues never did.

Ideologists are dangerous because, while “the opinions of intellectuals might be an adjunct to sound government but are no substitute for it.”

The Russian Revolution was prepared by theorists who were able to persuade themselves, in a period of chaos, that their theories would be put into action. But the only political theories worthy of the name are descriptive, not prescriptive. If prescriptive theories have plausible hopes of filling a gap left by a decayed or undeveloped institution, the game is already lost.

Amen to that.

¶ The penultimate Blogging Hero is Steve Garfield, of Steve Garfield’s Video Blog. Long after the rest of Blogging Heroes has become simply superseded, this chapter will retain a certain historical interest, as it captures a moment in time fairly comprehensively. Mr Garfield rattles off a list of vlogging tools that’s sure to stale very quickly — or not!