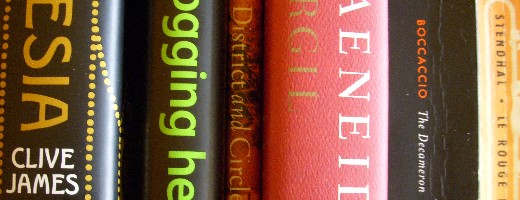

Morning Read

¶ Oy! You know how it is: you know you’ve read something somewhere before — but where?! Decameron V, viii lays a comic story on top of a very grim one, and I know that I’ve encountered the grim one within the past year or so. The setting was Kazakhstan or one of the other big former SSRs, and I thought I might find it by flipping through Gary Shteyngart’s Absurdistan. No joy.

In the grim story, a knight whose unrequited love drives him to suicide is condemned to hunt the woman who rejected him. His mastiffs tear naked her flesh from her body until she falls, whereupon the knight delivers an ugly coup de grâce. The show over, it immediately resumes.

In the comic overlay, a rich young man who is also pining for love is sojourning out of town. One Friday afternoon, he takes a walk in the nearby pinewood and witnesses the grisly spectacle of the hunting knight. This is where most tales would draw back, leaving the young man to draw some edifying conclusion. But Boccaccio is much too gregarious for that. His young man intervenes, scolding the knight for his grossly unchivalrous conduct. When the knight explains the situation, the tale becomes even more improbably comic (although no one will be laughing), for the young man resolves to harness the mayhem, which, after all, is really just a kind of natural resource, to teach his own lady-love a lesson. He orders a grand banquet for the following Friday, with the tables to be set up right there in the pinewood, so that all his guests — the young lady among them — will have ringside seats for the brutal ennesimo re-enactment. It works!

So great was the fear engendered within her by this episode, that in order to avoid a similar fate she converted her enmity into love; and, seizing the earliest opportunity (which came to her that very evening), she privily sent a trusted maidservant to Nastagio, requesting him to be good enough to call upon her, as she was ready to do anything he desired. Nastagio was overjoyed, and told her so in his reply, but added that if she had no objection he preferred to combine his pleasure with the preservation of her good name, by making her his lawful wedded wife.

On top of all this, Boccaccio cannot resist plopping a cherry: as a collateral benefit of this happy outcome, “the ladies of Ravenna in general were so frightened by it that they became much more tractable to men’s pleasures than they had ever been in the past.”

As editor and translator G H McWilliam points out every now and then, it is quite mistaken to think of Boccaccio as a proto-feminist.

¶ In the Aeneid, a skirmish breaks out between the Trojans and the Latians, and King Latinus finds himself between a rock (the oracle of Faunus, foreseeing victory for Aeneas) and a hard place (the wrath of Juno). He shuts himself up in the recesses of his palace, obliging Juno herself to crack open the Gates of War.

Is Virgil a passive-aggressive poet, cryptically reveling in the “naked steel” and din of battle? Or is he just dishonest, in love with peace (which he always describes so beautifully) but stuck with a story that demands the hostile confrontation that is war?

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, a lengthy hour in the salon of the Marquis de La Mole. Julien is mystified by the witlessness of the conversation, but Stendhal takes pains to show that the bright young things who sit behind the Marquises “vast bergère” are speaking in code — like young people everywhere.

It is difficult to navigate the blizzard of irony that rages through so much of this novel. I can tell that Stendhal is “being funny,” but I can’t tell exactly how, or to what extent. There is the further frisson of knowing that the world that Stendhal is describing was on the point of collapsing: the reign of Charles X, last of the Bourbons, came to end during the composition of this latter half of the novel. One could not be further distant from the settled milieux of Trollope’s fiction, where the bustle of politics never chafes at the texture of everyday life.

¶ Clive James on Sophie Scholl — the dissident activist whom the Nazis guillotined in 1943 — but really on the fabulosity of Natalie Portman. Having daydreamed about an adaptation of the White Rose story serving as a vehicle for Miss P, Mr J takes it all back.

And that’s where the dream movie falls apart, because if Natalie Portman plays the role, the girl won’t die. Natalie will go on after the end of the movie with her career enhanced as a great actress, whereas Sophie Scholl’s career as an obscure yet remarkable human being really did come to an end. The Fallbeil (even its name sounds remorseless — the falling axe) hit her in the neck, and that was the end of her. Her lovely parable of a life went as far as that cold moment and no further. It’s a fault inherent in the movies that they can’t show such a thing. The performer takes over from the real person, and walks away. For just that reason, popular, star-led movies, no matter how good thye are, are a bad way of teaching history, and you don’t have to be an oaf to get impatient when they try to.

I agree, very strongly, about the inbuilt inadequacy of film as a teacher of history. But it’s an unsurpassed illuminator of history — especially when it gets things wrong.

¶ Today’s Blogging Hero: Gary Lee of Mr Gary Lee: An Internet Marketing Web Site. The most incomprehensible chapter so far. Googling for a definition of the concept, “link train,” I came across this earnest and affable video, which rather made me feel like a bedraggled emissary of the Emperor of China, creeping back from a European voyage and trying to make sense of the theological disputes of the Reformation.

Only five more bloggers to go!