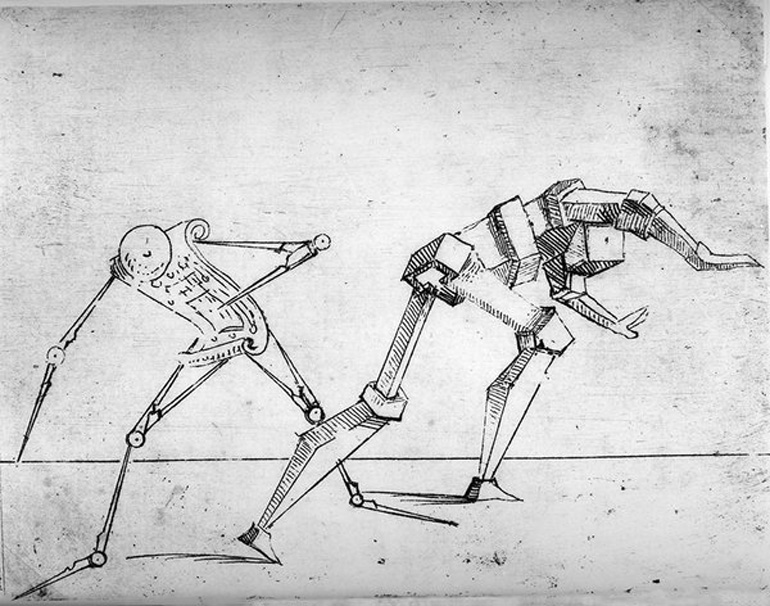

It’s an extraordinary image, isn’t it? Especially if you know that, the work of one Giovanni Battista Bracelli, it dates from 1624, nearly three hundred years before the word “robot” was introduced. I copied it from the current issue of the New York Review of Books, where it adorns Sue Halpern’s review of Nicholas Carr’s The Glass Cage: Automation and Us, a piece that I referred to yesterday. The figure on the right is very dramatic — reminiscent, for me, of Paul Taylor’s dance, Cloven Kingdom. But it’s the figure on the left, composed in part of six compasses, that tickles me. Six compasses, a bit of baroque scrollery, and what looks awfully like the bells mounted in school hallways. Done!

It can’t quite go without saying that these drawings do not anticipate robots, but rather create (or further), in the venerable tradition of capricci, or fanciful doodles, the imagery to which illustrators would recur when robots did arrive, as fancies of a rather different kind. Bracelli’s characters are not anthropomorphic but just the opposite; they envision men with the gift of fleshlessness. These fellows stumble around painfully, but they will never bleed. It is difficult to suppress the idea that Bracelli’s drawing is “futuristic,” but we must make the effort, and not only because popular illustrators tasked with creating “futuristic” designs drew on very old ideas (if not necessarily Bracelli’s drawing itself). Futuristic images are so rarely predictive.

***

I thought about running the picture atop yesterday’s entry, where it might have been more apposite, but I’m glad that I didn’t, because I see it more clearly than I did yesterday, now that I have read The Buried Giant, Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel. The Buried Giant is also about images and their recurrence. This is not immediately obvious — as I must conclude on the basis of two of the four reviews of the novel that I read as soon as I was done with it. (I plead guilty to the charge of reading The Buried Giant, somewhat against my current inclinations, simply in order to deal with the reviews that were piling up, and that I could not read until I knew the book itself.) These rather unfavorable reviews, by Joyce Carol Oates and Adam Mars-Jones, appeared in the two Reviews, New York and London respectively. Oates and Mars-Jones are fairly unhappy to find that The Buried Giant is remarkable neither as a narrative nor as a piece of writing. In their disappointment, they dismiss the novel as second-class fantasy. (Mars-Jones is by far the harsher. Of the novel’s most stirring action sequence, he writes, “From the reader’s point of view, it’s like excavating the supposed site of a medieval abbey and discovering the ruins of a multiplex cinema.” This judgment is not nearly as clever as it sounds.)

The other two reviews that I had on hand, by Christine Smallwood, in Harper’s, and Nathaniel Rich, in The Atlantic, were favorable. Smallwood’s piece is a conspectus of “Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels of remembering” (as the subtitle has it), and at least it left me feeling that I wasn’t a complete fool to have enjoyed The Buried Giant. It was Rich’s piece, however, that woke me up to what I’d liked about it.

From subsequent clues, we can deduce that the year is approximately 450 AD, but despite our unnamed narrator’s anthropological tone, we are not in England as it actually was then, but as it was imagined seven centuries later by Geoffrey of Monmouth and the other mythologizers who gave us King Arthur, Sir Gawain, and the wizard Merlin.

This is exactly right, and I shall try to explain why it is also very interesting.

In The Buried Giant, the people of Britain — the “Briton” (Celtic) and Saxon inhabitants of the island — are afflicted by a kind oblivion that, in Ishiguro’s hands, is pregnant with thought about the nature of memory. This oblivion, unlike the cruel caprice of Alzheimer’s Disease, does not make its victims forget their own names, or the faces of their loved ones. They simply forget what is no longer around to remind them — a bit more quickly than we all do. Axl and Beatrice, the elderly couple at the center of the novel, cannot remember why their son no longer lives with them; they decide to set out to visit him even though they have no idea where that might be. The implication is that Axl and Beatrice no longer remember that the world, even the world of England, is a big place. Beatrice occasionally visits a Saxon settlement that is about a day’s journey distant, and she seems aware of other villages that lie beyond it; surely their son lives in one of these. So their adventure begins, and it soon becomes a quest — Beatrice’s quest — to put an end to the cause of this oblivion. Beatrice believes that recollection will bring understanding, and Ishiguro maintains our loyalty to Beatrice even as he makes it clear that recollection will bring other, much less desirable things, most notably the longing for revenge.

When what literary historians used to call the matière de Bretagne, the bundle of stories surrounding a late-Roman warrior known as Arthur, were being polished for courtly appreciation by poets and “historians” like Geoffrey of Monmouth, in the middle of the Twelfth Century, there was no real evidence of who the important people of 450 might have been. There were no documents, no inscriptions, no tombs. Bit of weaponry and coinage and other such knickknacks told an ethnological, but not an historical, story. Instead of the kind of evidence that modern historians insist on, Geoffrey and his French counterpart, Chrétien de Troyes, had stories, oral ballads one supposes. We don’t know much (if anything) about how twelfth-century writers transformed this matière into the written works that have come down to us, not because the process was embarrassing but because it was of no interest.

There was no critical voice asking Geoffrey to produce his sources. Geoffrey’s job was to create a satisfying account of what no one doubted — for everyone was familiar with parts of the matière — must have taken place. It is certainly arguable that Arthur and Merlin were “based,” over generations of retelling, on men who existed in 450, but those men were not like Arthur and Merlin. Arthur and Merlin, like snowflakes, grew during and were shaped by centuries of changing conditions. By Geoffrey’s day, a line had been drawn beneath most of those centuries by the Norman Conquest. The old changes, from Roman to Saxon Britain, were over.

Like the villagers among whom Axl and Beatrice live, at the beginning of The Buried Giant, the men and women who “retold” the stories that became the stories of Arthur and Merlin had forgotten everything about the great warriors of the mid-Fifth Century — everything but that there had been great warriors. The stories were the product of oblivion. Kazuo Ishiguro, studding his new novel with ogres, pixies, and a she-dragon, is perfectly aware of this, and he assumes that his readers are perfectly aware of this, too. His she-dragon is not the sort of accoutrement of fantasy literature that it would be in Tolkien. It is a small monument not only to the inability but also to the unwillingness to remember that no one has ever seen a she-dragon.

***

I have always thought of Ishiguro as a “Japanese” novelist, complete with scare quotes. I know that he grew up and was educated in England, and that he did not revisit Japan (having left it at the age of five) until he was an adult. What I mean by “Japanese” is a synthetic, imaginary quality that is self-consciously imitative of illustrious exemplars. It supposes an aesthetic at odds not so much with Western practices of art as with Western ways of talking about those practices. The Western artist is thought to require “new forms.” He goes out into the garden and looks closely at a peony blossom. He studies it to the exclusion of every other consideration. Then he returns to his studio and paints what he saw: his vision of a peony blossom. The Asian aesthetic, embodied in such treatises as The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, assumes that you must know how to paint a peony blossom before you can actually see one. Therefore you must study all the best paintings of peony blossoms before you consider an actual flower on your own. When you paint what you saw, you strive to make it look as much like other, great, pictures of peonies as you can. If you, too, are blessed with greatness, this will manifest itself almost as an error, as a falling-short of the exemplars, or, just as problematic, a falling-beyond. Your peony painting will be judged only by connoisseurs, men who may or may not be painters themselves but who are familiar with all the exemplars.

I don’t think that Western art is much different, but ever since Vasari, it has been presented in terms of progress and advance. Connoisseurs know better. Or, rather, they understand that “progress” and “advance” have nothing to do with beauty, and are therefore of no interest.

So what I mean when I say that Ishiguro is a “Japanese” artist is not that he has embraced the culture of his ancestors, but simply that — helped, perhaps, by an awareness of that culture — he has dumped a lot of European claptrap. His books, even the most gripping ones, are never about new forms. On the contrary; they are studies of old forms. Christine Smallwood, wondering why, as a “recent convert,” so many of her acquaintance either think little of Ishiguro or take him for granted without content, quotes a letter from a friend.

I think he’s very good, yes, although to be honest there is something snobbish in me that never quite lets myself say he is one of my favorite writers. What is that? I think it’s something about feeling very clearly manipulated, maybe.

That’s our world in a sentence: the writer is too much a snob to admit being the kind of snob who might be called a connoisseur: someone who cannot be manipulated. The big difference between Europe and Asia in this regard is that, in Europe, people who don’t know much about anything will be heard, their opinions “respected.” I hope that I don’t sound too much like Nietzsche when I say that this is ridiculous nonsense.

The pleasure of reading The Buried Giant is very much that of the connoisseur. This can be described in two ways. Positively: the connoisseur grasps a network of objects that becomes more powerful, and even overwhelming, as more connections are made. Negatively: connoisseurship is derivative, preoccupied with the past; ultimately, the connoisseur becomes an oppressive, completist bore. The difference is temperamental, and I don’t see the point of trying to convince people who are impatient with connoisseurship that they are wrong. The pleasure was in any case genuine for me. During the action sequence that I mentioned earlier, I was remembering the excitement of the climax of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose — both scenes of tumult in a monastery; but I was also remembering the fractured narrative, which I didn’t enjoy at the time, of Robert Coover’s Pinocchio in Venice. I was often reminded of Boccaccio, because the archaic style of dialogue adopted by Ishiguro is that of translations of the Decameron — musty and earthy, with nothing left out or taken to be understood. This very quality also reminded me, but negatively, of the King James Bible, a book of many mysteries. If I did not, like the reviewers, make a connection between Ishiguro’s Sir Gawain and Lewis Carroll’s White Knight, that is because, to my shame, I am not conversant with the Alice books. (And if Monty Python and the Holy Grail occurred to me at all, it flashed by very quickly, because I should never allow satire, no matter how exhilarating, to cause collateral damage.) It’s probably no accident that I was reminded of many things that I can only halfway recall; I am no model connoisseur. But the pleasure of sensing connections was constant and quite intense.

I have been describing what I consider to be Ishiguro’s overall style, which I call, cheekily, “Japanese.” What makes The Buried Giant distinct, and not just a medium for memories, is its ongoing dramatization of memory and memory loss. What I mean most by “dramatization” here is that neither memory nor its loss is an absolute evil, the bad man in the play. Axl, who only dimly remembers that he and Beatrice may have had violent disagreements in the past, causing one another pain and even estrangement, wonders if oblivion has not, by healing those old wounds, allowed his love for her to grow robust and even indomitable. The Saxon knight, Wistan, with whom Axl and Beatrice travel — Canterbury Tales! — wants to put an end to the oblivion precisely to sharpen his people’s resentment against the untrustworthy Britons, who, as we know historically, will be beaten back beyond the marches of Wales and the borders of Scotland. We can argue, with Beatrice in turn, that understanding removes the sting of memory: tout comprendre est tout pardonner, a maxim that the Holocaust, however, appears to have derailed. There is no getting to the bottom of this conundrum, because there is no getting to the bottom of the fact that we are little more than what we remember, and that we shall all disappear in the oblivion of others. What makes The Buried Giant exciting to read is the unceasing prospect of betrayal: whom can Axl and Beatrice trust? Can they even trust one another? This, too, is a problem of memory, for we cannot remember what has not yet happened. We can only remember, and that very imperfectly, what has happened in like cases. For the experienced reader, the number of like cases is immense, and Ishiguro’s low-key prose does little to steer you among them.

The Buried Giant ends on a quay by a river, across which lies a special island that can be reached only by the offices of a ferryman, and the ferryman can carry only one passenger at a time. The hope nursed by Beatrice and Axl, that an exception might be made in their case, and both might be ferried across in a single crossing, is as heartbreaking as the hope of those Hailsham students, in Never Let Me Go, that love calls for the special treatment of lovers. It is so easy to forget that love is itself the special treatment.