Wednesday Morning Read

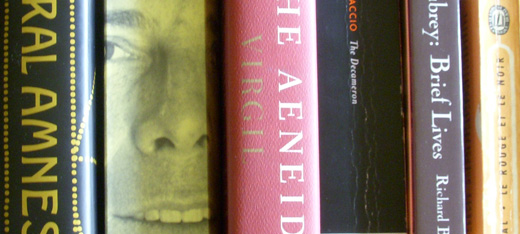

¶ In the Decameron, a sort-of Robin Hood story, involving a brigand and the Abbott of Cluny. Did I say “brigand”? Ghino di Tacco comes off as a Mafia don. As for the Abbott, I remember him: he appears in I, vii.

On the whole, I find Boccaccio’s anecdotes from real life to be somewhat disappointing. I much prefer the tales that, even by Boccaccio’s day, had been handled to a fineness.

¶ In Aubrey: Petty, Philips (Fabian), Philips (Katherine), Platers, Pointz, and Pope. Unusually miscellaneous stuff, even for Aubrey. The life of Sir William Petty — admittedly, a man of many parts — is totally scatterbrained, but full of entertaining nuggets. “John Gadbury also says that vomits would be excellent good for him.” Bad for the teeth, though. Early on Aubrey tells the story of a challenge that Sir William parried wittily; then near the end, we have this paragraph:

Enquire for the name of the knight his antagonist, Sir…. Answer: ‘Twas Sir Hierome Sancy that was his antagonist; against whom he wrote the octavo book, about 1662. He was one of Oliver’s knights, a commander and preacher and no conjuror. He challenged Sir William to fight withhim. Sir William being the challengee [remember, Aubrey has already told us all of this] named the place, a dark cellar, the weapon, a carpenter’s great axe; so by this expedient Sir William (who is short-sighted) would be at an equal tourney with this doughty man.

But he neglects to repeat, “This turned the knight’s challenge to ridicule, and so it came to naught.” Appended to the life of Sir Robert Pointz is the following tasty but irrelevant morsel: “Memorandum: Newark (now the seat of Sir Gabriel Lowe) was built by Sir Robert’s grandfather to keep his whores in.” About Sir William Platers we learn not only that he “was a great admirer and lover of handsome women, and kept several,” but that he procured same for his son as well. His son’s death in the Civil War took the zest out of life for Sir William’s.

¶ Serge Diaghelev provides Clive James with a pretext to discuss the living arrangements of various creative geniuses. “At one extreme, some pour all their creativity into their art and don’t care how they live. At the other, there are those who have to arrange their personal lives at a certain aesthetic level before they can function.”

In all of literary history as we know it, perhaps the most outstanding slob was W H Auden. The man whose lyrics were showpieces of carpentry — try to imagine a poem more accurately built than “The Fall of Rome” — kept a kitchen that would have doubled as a research facility for biological warfare. Worse, he treated other people’s houses the same way. Mary McCarthy, when a guest, earned a bad reputation for taking a long shower with the curtain outside the bath instead of inside: the host would receive no apology for the subsequent inundation. From Auden, a mere flood would have counted as a thank-you note: he left his benefactors under the impression that they had been visited by the Golden Horde. Auden lived long enough for me to see his tie. I thought it had been presented to him by Jackson Pollock until I realized that it was a plain tie plus food. It put the relation of writer to written in a new light.

Neglecting Merrill for a day, I found it strangely squinting to proceed directly from Aubrey to James, what with both writers’ being so generous with anecdotes.