Monday Morning Read

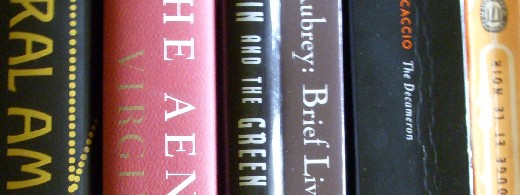

¶ In the Decameron, VII, iv, Boccaccio once again strikes what seems to be “the moral of the story.” After the wife makes a fool out of her jealous husband, he has to win her back by promising to trust her in a different key, as it were.

And not only did he promise her that he would never be jealous again, but he gave her permission to amuse herself to her heart’s content, provided she was sensible enough not to let him catch her out.

… alla quale promise di mai più non esser geloso, ed oltre a ciò, le die’ licenza che ogni suo piacer facesse, ma sì saviamente, che egli non se n’avvedesse.

Christendom (such as it is) remains of two minds on the point. Where the objective is purely charitable, such deceptions are called “discretion.” It’s only when carnal pleasure enters the picture that we talk of “cheating.”

¶ In the Aeneid, the deaths of Euryalus and Nisus. Not gay at all but quite homoerotic.

Nisus dying just as he stripped his enemy of his life.

Then, riddled with wound on wound, he threw himself

on his lifeless friend and there in the still of death

found peace at last.                            How fortunate, both at once!

If my songs have any power, the day will never dawn

that wipes you from the memory of the ages, not while

the house of Aeneas stands by the Capitol’s rock unshaken.

Virgil appears to hope that his listeners’ taste for epic verse and legend will extend to other Greek proclivities.

¶ In Aubrey: Camden (the antiquarian), Canynges (an alderman of Bristol who left many fine buildings behind when he died, rather out of Aubrey’s period, in 1474), Cartwright (poet and playwright), Carey (a Viscount Falkland with a popish mother named Letice), two Cavendish cousins (Charles, of the Devonshires, and William of the Newcastles), and Cecil, Lord Burgley — Elizabeth’s great statesman. D’you know, I’d always wondered about the name “Cecil,” which seems too good to be true, as indeed it is:

¶ I have often admired, that so wise men as the Lord Burghley and his sons were, should so vainly change their name, that is from that of Sitsilt, of Monmouthshire, a family of great antiquity. … And Mr Verstegan (otherwise an exceeding ingenious gentleman) to flatter this family, would have them to be derived from the Roman Caecilii; whereas they might as well have been contented with the real antiquity of this and Monmouthshire, and needed not to have gone as far as Italy for it.

“Sitsilt”! Imagine someone trying that out on the Marquess of Salisbury!

¶ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, I conclude, was not really a book for the Morning Read. I ought to have swallowed in two or three sittings at the most. It is not a work to linger over — not the first time through, that is.

I never did see it coming. I didn’t see that the lord of the castle would turn out to be the Green Knight, hexed by Morgan le Faye, the old lady who accompanied his wife. I was gratified, though, by Gawain’s remorse for having kept the “love-lace” to himself.

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, we find ourselves in the typical affluent American high school.

Son mot si franc, mai si stupide, vint tout change en un instant: Mathilde, sûre d’être aimée, le méprisa parfaitement.

I’m beginning to wonder if my Livre de poche edition, which I’ve been carting around, unread, since 1973, is going to make it through the “reading process,” physically.

¶ I had fond hopes that Clive James would explain Ludwig Wittgenstein to me, but I came away convinced that I still miss the point. The point of what, exactly? Well, that’s the problem, exactly. I don’t know what I’m missing when it comes to modern philosophical inquiry. I could run through a paragraph of clichés to that effect.

What calls me is that this obscurity lies beyond the benchmark. The benchmark is sports. I don’t know why people can’t think of something better to do than follow team sports — and by “better” I mean a fanfold of possibilities: something more personal, something more responsive (“interactive” is the modern word), something — most of all — linear rather than cyclical (in that following sports is not very different from following soap operas) — but I see what it is that draws them. The action, the excitement, the uncertainty, even the occasional grace. Also, the tribal piety of following a team.

When Clive James reduces Wittgenstein’s later thought to the truism that “an expression has meaning only in the stream of life,” I wonder what sort of rubbish had to be cleared from the brain in order to make this apparent. I do not see the foundation of a philosophical outlook. James weasels off, as he tends to do when the analytic temperature rises, in praise of the virtues of Wittgenstein’s gift for aphorism: from philosophy we revert to a topic that’s as dear to me as it is to him, the mastery of reading foreign languages. Sometimes what’s worth noting isn’t that the emperor’s clothes are “transparent,” as if this were interesting. Sometimes, the emperor is just a guy.