Gotham Diary:

Snobbery Doesn’t Come Into It

December 2015 (V)

Monday 28th

At the end of her remarkable little book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Marie Kondo writes that it is not for everybody.

You won’t die if your house isn’t tidy, and there are many people in the world who really don’t care if they can’t put their house in order. Such people, however, would never pick up this book. You, on the other hand, have been led by fate to read it, and that probably means that you have a strong desire to change your current situation, to reset your life, to improve your lifestyle, to gain happiness, to shine.

This sort of thing usually appears at the beginning of self-help books, not on the penultimate page. Placed where it is, however, the statement about “you” is not just an alluring promise but a demonstrated fact. Well, it was for me, partly because I have, in my somewhat longer life, stumbled on a few of “KonMari’s” home truths already. I felt an enormous affirmation of all my housekeeping intuitions. This was all the more welcome for coming in the middle of a dark time, a screwed-up holiday season.

Life-Changing Magic preaches the importance of taking things seriously — the material things that crowds your closets and drawers. If they are truly important to you, if, in KonMari’s quaintly off-sounding phrase, they “spark joy,” then by all means keep them. If they don’t, then their importance consists in the need to get rid of them, no matter how profuse the excuses for retention. Once you have purged your life of things that fail to spark joy, you will find it easy, she promises, to find the places where everything that you keep belongs.

There is no need to buy anything. There may not even be the need to buy the book, because KonMarie encourages her readers to discard things that have served their purpose, and you might know one such reader. KonMari believes that you probably already possess more than enough of the storage equipment that you need — drawers, shelves, closets, and so on. The only thing that is required to make a success of her challenge is your attention. You must pick up everything that you own, one at a time, and attend to the feeling that holding it brings.

The end result is not a tidier home. It is a more sharply-focused sense of self. The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up is essentially a diet book, addressed to the thin person inside anybody who feels fat. This metaphorical fat is actual confusion. We have amassed heaps of stuff because we might find it useful. We intend to read this book when we have time, or to use that pot when the right party is on the calendar. You never know. You never know whom you might want to become, when you’ll need the right stuff.

This “never knowing” is obviously confusing, a cloud over your grasp of the future, such as it is. KonMari’s simple test is this: does the person that you want to become make you happy now? One of her favorite categories of clients’ discards is study guides for speaking English. Everybody seems to have a few of these, but the books never spark joy. Does this mean that speaking English is unimportant? Yes. For most people, speaking a foreign language is an accomplishment, like playing the piano. If you are passionate about it, you just do it. If you’re not, it means that you’re happy with your life as it is, but are cluttering it up with insincere aspirations. Once you clear your home of the material litter of these fond hopes, you will find the true ones. KonMari mentions a woman who pared down her library until it told her what she wanted to do with her life: When the only books left were all concerned with social work, she decided to launch a day-care center.

Modern life is characterized by cheap plenty. Just as there is too much flimsy clothing, and too much processed food, so there are too many options for “personal realization.” The odiously-named concept of the bucket list implies that life is not lived without certain special experiences. Most of these experiences are passive, even if they involve a bit of exercise. (Climbing the Eiffel Tower is possible only because Monsieur Eiffel actually built it. “The Eiffel Tower” belonged on his list in a way that it can’t on anybody else’s.) They are as inconsequential as postcards — for what, after all, does seeing the Grand Canyon bring to your life beyond yet another wow? It were better to study your local geology — better not to spend time and resources for an idle glimpse of some remote wonder. The best of these lists would include only one goal, and achieving it would be both difficult and fulfilling. It is hard to determine that one goal, however, if your house is full of how-tos.

Find out who you already are, and get better at it. Throw away all the stuff that who-you-are doesn’t need.

***

As it moves along, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up takes on a tone that some readers will find “spiritual,” not meaning it as a compliment. KonMari talks about welcoming her house when she comes home from work. She thanks the things that she throws away for having given her the pleasure of acquiring them, which was, apparently, all they were good for. She folds her clothing with something like reverence. Once she has presented her businesslike criteria for filling garbage bags, she lets her house tell her where everything that she retains belongs. This will certainly strike some readers as silly and new-age-y. Others might see the heritage of a Zen-like respect for the world. KonMari explicitly wants her house to have something of the sacred aura of a Shinto shrine.The secular reader in search of housekeeping tips might find this sort of thing annoying.

Asian thought, however, has never made a significant distinction between the material and the metaphysical; the spiritual world does not lie outside or beyond the one that we apprehend with our senses. There is little or no Platonic dualism. So it is entirely reasonable, in such an intellectual climate, to hold that material things, far from being vain appearances, can touch our souls. In fact, it is urgent that we recognize and accept this un-Reasonable proposition, because it is the central insight of environmental respect. The quality of the world in which you live influences the nature of the person you are.

Human beings have almost always acknowledged this, but with a fateful backwardness. If you were poor and uneducated, that was your destiny, and nothing that anybody else could help change. Perhaps it was necessary for some people to become rich and learned, just to see how far human capability might be stretched. Once that was discovered, however, and once it was at the same time discovered that most rich and educated people don’t stretch their own human capabilities very much at all, it was clear that, one day, the talk of destiny must be abandoned, and a world of more equitable distribution conceived. We are still a long way from any such achievement, and I don’t see any social tools that would realize it soon. Today, however, we have a peculiar problem. Because some people manage to organize their way out of wretched environments, we like to think that everybody living in poverty might do the same. In fact, the few who do emerge are as unusual as the figures who long ago became priests and kings, in the early days of agriculture. Ordinary people who happen to be disadvantaged need good-enough food, clothing, and shelter no less than others; above all, they need to be spared the terrible stress of being poor, the endless and exhausting decisions that navigating a hard life entails.

These are people who don’t need Marie Kondo’s book.

For those of us who do, the insistence of the connection between the world outside and the soul within is the same, despite our bland comforts. Affluent people are no less embroiled in the world around them than are the poor. Their inclination to believe that they can take or leave that world, that the freedom to do as they please assures that they will be who they please, is sadly mistaken. It is perhaps unintelligent to argue that we are all the products of the world we live in, but there is no doubt in my mind that we live in dialogue with it, and that conducting this dialogue with humility and respect will make the world a better place.

***

Tuesday 29th

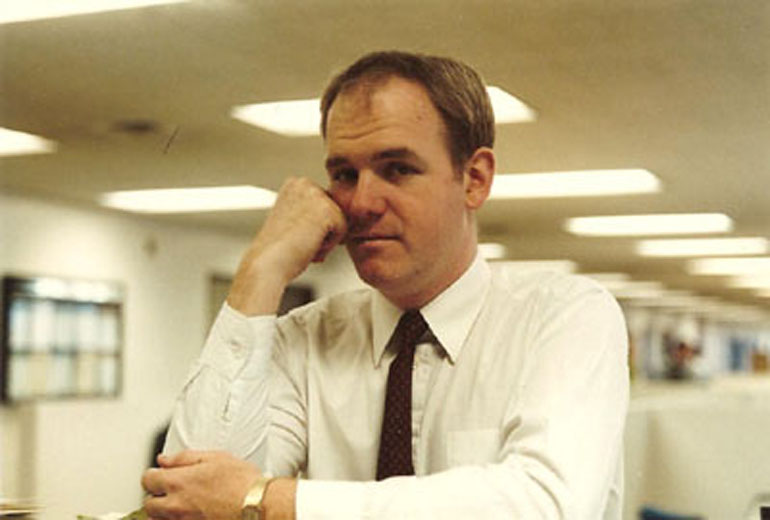

Never having gotten round to selecting a photograph for this week’s entry, I forgot to post yesterday’s opening. This morning, I rooted around old pictures for half an hour, finally settling on something from a long time ago, a picture that someone took of me at work, shortly before or after Kathleen and I were married. So we end the year with a salute to the past, which is definitely another country.

Our trip to San Francisco is off. Kathleen is simply too swamped, doing the work of two lawyers; besides, there might be a new client in the offing. I thought, very briefly, about traveling alone, but that’s something that I haven’t done in more than fifteen years. I might travel with someone other than Kathleen, but not alone. And I don’t think that I’d leave Kathleen alone just now.

***

In passing, yesterday, I declared that mastering a foreign language is an “accomplishment” for most people, meaning that it is not vitally important. This judgment might seem at odd as with the genius loci of this Web log. I believe that the ability to read foreign languages is vitally important to all educated people, and even more to the society in which they live. We need as much experience as we can get of other ways of thinking, and I believe that this experience is best encountered in printed matter.

Growing up the Cold War, however, I was habituated to the drudgery of what were called language labs — rooms with cubbyholes, tape recorders, and headphones. To learn a foreign language meant to speak it. Reading it, especially reading it as literature, was secondary. The entire enterprise, I’ve since decided, was baloney. You can learn to speak a foreign language in an intense, immersive course, but you will not hold onto it, or make it part of your life, unless you spend some time — at least six months, I should think — living in a place where it is the spoken language. It would be wonderful if everyone had the opportunity to spend some time somewhere abroad, and I’m sorry that I missed my chance in college (although I was much too immature). But without such sojourns, a foreign language cannot be absorbed.

We ought to go back to the pedagogic idea that prevailed before the Cold War, when foreign languages were needed mostly by scholars who had to keep up with foreign scholarship. Learning to read a foreign language is much simpler than learning to speak it, because mere reading does not require you to stop thinking in your own — a bruising experience. Mastering a foreign grammar, as is far more necessary for reading than for speaking another language, probably gets in the way of learning to speak it, because vernacular speech everywhere is usually quite ungrammatical (or at least a-grammatical). But speaking a language will take care of itself, when the actual need arises. You will certainly not learn a foreign language better by studying it at home than you will if you’re surrounded by native speakers.

The effort to speak foreign languages is actually making us all more illiterate than we might be.

***

Another bit of received wisdom that has fractured for me in recent weeks can be formulated thus: the loss of religious belief has left modern man alienated and rootless, in constant but hopeless search for substitutes.

To the extent that this is true, it is true, I believe, only of highly educated people — people who formerly experienced religion as a source not only of spiritual meaning (I’m very uncomfortable with this phrase, but it turns up all the time in the received wisdom) but also of material explanation. For people who lost religious belief, the challenge of scientific explanations of the world not only dismantled their religious counterparts, as elaborately expounded by Thomas Aquinas, but undermined spiritual meaning as well. This didn’t have to happen; there are still plenty of people walking around today who believe in (the Judeo-Christian) God without discrediting science. Many of these people are highly educated.

As for uneducated people who have stopped going to church, it’s less likely that they lost their religious belief than that they are enjoying a modern liberty. If anything has changed since the old days, it is the license that our constitutional insistence upon religious freedom has given to people who want to sleep late or pursue a hobby, instead of attending religious services. This is new. You used to have to participate in the local religious rites, whether you wanted to or not. When the going gets tough, ordinary people will return to their pews — if they’re not setting up some new sect.

This, I think, is the root of the élitist anxiety about the alienation of the common man: what the common man has become alienated from is the idea that he ought to do what élitists tell him to do.

But élite alienation is much more serious. The loss of religious belief among élites is quite real, particularly among those sections of the élite that frame leadership propositions. For it must be understood that nobody has become alienated from the need for leadership. The problem is that, without some kind of divine backup, élites doubt their own authority to formulate responses to social problems. Élites throughout history have claimed supernatural support for their proclamations of what must be done. But God was divided in the Reformation — torn apart, literally; the élites of a very small portion of the earth’s surface could no longer agree on just what it was that God wanted. During the century following the demoralizing end of the Thirty Year’s War, in which Catholic Austria refused, refused, and refused again to recognize the claims of Protestant Germany, better minds devoted themselves to weighing the possibility of detaching Western élites from God.

They got no further, really, than insisting that there must be a detaching. Reattachments to other alleged sources of meaning and authority, such as art or education, have not succeeded. On the Times’s Op-Ed page, believers such as David Brooks and Ross Douthat assert, more or less emphatically, that reattachment is impossible; only the old, the traditional source of morality — Judeo-Christian scripture — will serve. (This is, after all, God’s world.) Most members of the élite — journalists, particularly — are agnostic and even self-denying. All but the most aggressive investigative journalists are uncomfortable with the claim that their reports are morally authoritative. This is particularly true in political reporting.

What constitutes leadership today? That is the very important question that lurks behind the limping complaint about “alienation.”

With the advent of nationalist, populist democracy in the Nineteenth Century, élitists found themselves to be unwelcome, for it was populism’s mad dream, wholly anticipated by the political philosophers of classical antiquity, that societies could function without élites. (Libertarianism is nothing but populism for nerds: Silicon Valley presents the comical spectacle of men (mostly men) who not only want to sweep away conventional existing élites but who regard themselves as smart guys just doing their own thing and telling no one else what to do. Just conducting orgies of creative destruction.) The emergence of an élite is just about the first thing that happens in any society.

With traditionally-trained élites ruled non grata, the nationalist democracies exposed themselves to the antidemocratic tyranny of charismatic leaders who made things up as they went along, trailing chaos and bloodshed. We were given good reason to fear the very idea of leadership. That may explain why, in all the long decades since the deaths of Hitler and Stalin, little has been done to configure the profile of a truly democratic leader. Thoughtful Americans recognize how lucky they were to have FDR — and how useless he is as a template. In any case, our leadership models are all deformed by the deadly crises that called them forth. Who was Churchill without the Nazis? An impetuous, imperialist windbag.

Fortunately, the idea of a “peacetime” leader need not detain us. We are not living in peacetime. Quite aside from the political confusions that disrupt the élite’s globalist dreams, there is the uncertain urgency of confronting environmental degradation, and the certain urgency of doing so with a patience capable of resisting apparent solutions that will only derail society.

I don’t think that we need God to inspire us to behave better than we do. I don’t think that we need the attractions of resurrection and eternal life to rivet our attention to saving ourselves from possibly immediate immolation. But we do need good leaders.

At the dawn of our industrial, then technological era, it was not unusual to hear oracular declarations that man had displaced his gods. It may be the greater part of the élite has lost its faith in supreme beings. But I doubt that there are any serious members of the élite today who entertain such orgulous notions. Lost faith in God may never be replaced, but neither will God.

***

Wednesday 30th

As everybody knows, the first issue of the London Review of Books for the new year features a presumably abridged edition of Alan Bennett’s diary for the year. The entries are superficially short and slight, until you read them. Humour, wisdom, a very dry nostalgia; a bemused affection for relatively unsophisticated parents — Bennett was surprised that his father found Nancy Mitford very funny. This year’s big event was the opening (or openings) of The Lady In the Van, which occasioned a trip to New York last month. In preparation for this, Bennett sprained his ankle. He was flown First Class across the Atlantic, he tells us, by the New York Public Library (which was going to make him one of its Literary Lions) and by Sony Pictures.

I wonder, though, looking at our fellow passengers, who is paying for them, so ordinary do they seem and even scruffy. Perhaps they’re all in the music business, in which case this not being a private jet is maybe a bit of a comedown.

On the one occasion when I flew first class from London to New York, the scruffiness of my fellow high-livers was what struck me, too. But I didn’t have quite the wit — even if I did share the suspicions of the second sentence — to jump from looking too poor to be in first class to looking too rich, and to break through the pretenses of airlines in order to remind myself that really grand people don’t fly First Class any more. They fly Only Class.

Here is the entire entry for 1 September:

Oliver Sacks dies, my first memory of whom was as an undergraduate in his digs in Keble Road in Oxford when I was with Eric Korn and possibly, over from Cambridge, Michael Frayn. Oliver said that he had fried and eaten a placenta. At that time, I don’t think I knew what a placenta was except that I knew it didn’t come with chips.

I left college with an ironclad determination to avoid the Oliver Sackses of this world. People who fry and eat placentas, so that they can tell you about it. I had no idea that Sacks was gay until earlier this year, when he began dying in public, but when I saw the dust-jacket photo of him astride a motorcycle in Greenwich Village, looking as burly and butch as Bob Hoskins, I felt very sad. How many pointlessly thwarted lives! How much tedious transgression! Alan Bennett’s transgressiveness, in contrast, is genial even when it is tinged with bitterness.

As it happens, Bennett puts his finger on the importance of tact in an early entry (15 February). He has just read some good reviews of a play, Blasted, given at Sheffield. (He seems to be a friend of the director.)

In such a violent play, though, I find myself spiked by my literalness … If a character is mutilated on stage, blinded, say, or anally raped or has his or her feet eaten off by rats, the pain of this (I nearly wrote the discomfort) must transcend anything anything else that happens on the stage. A character who has lost a limb cannot do other than nurse the wound, no other discussion is possible. Not to acknowledge this makes the play, however brutal and seemingly realistic, a romantic confection. If there is pain there must be suffering. (But, it occurs to me, Gloucester in Lear.) Another topic concerning me at the moment is Beckett’s sanitisation of old age about which, knowing so little of Beckett, I may be hopelessly wrong. But Beckett’s old age is dry, musty, dessicated. Do Beckett’s characters even smell their fingers? Who pisses? How does the woman in Happy Days shit?

There are two beautiful reconsiderations — what Bennett would or should have done had he known what he knows now. He now wishes, having just seen a revival of An Inspector Calls, that he had taken advantage of an opportunity to plug JB Priestley for the Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey; and he laments not have been sufficiently aware of it to remember hearing Kathleen Ferrier sing Dvorak’s Stabat Mater in 1950. (I, too, find that work both dreary and empty.) He had to be reminded by an old program. What he did remember was sitting behind the Princess Royal (soon to become HM the Queen) and her Lascelles relations. Well, who wouldn’t?

Whenever possible, Bennett heaps contumely upon the Tories. He does not say that he loathes David Cameron, but you get the sense that he does; yet when he says that he “did detest” Margaret Thatcher, you also sense that Cameron isn’t quite worthy of detestation, that he doesn’t measure up even as a villain. The remark about Thatcher (11 October) is provoked by Charles Moore’s recyling of Graham Turner’s “mendacious interview with me and other so-called artists and intellectuals in which we are supposed to have dismissed Mrs T out of snobbery.” Snobbery didn’t come into it, Bennett insists, because he and Thatcher arose from the same background. This ironic observation tickled me enormously, for while the Iron Lady may have impersonated Britannia during the Falklands War, in fifty or a hundred years she will only be read about, while Bennett will still be read. By the time Kathleen came in to get ready for bed, I had improvised a dactylic chanty:

For SHE was a GROcer’s DAUGHter from GRANtham,

And I was the SON of a BUTCHer from LEEDS.

Sadly — How very disappointing, I think Maggie Smith says somewhere in Evil Under the Sun — that’s not how Bennett puts it. He doesn’t mention Grantham or Leeds. “But she was a grocer’s daughter as I am a butcher’s son. Snobbery doesn’t come into it.” I do blunder so.

***

Friends from out of town will be coming to dinner tonight. They still share a family apartment on the Upper West Side, but they spend most of their time in Brewster, on Cape Cod. We have seen them only once since they relocated, and they have not been to this apartment. Which I shall be tidying up this afternoon. Dinner is “under control.” Also this afternoon, I shall make a soup of wild rice and mushrooms. I have already made a carbonnade. It filled the apartment with such lovely smells last night that I was afraid that all the flavor was dissipating. The secret, aside from a bottle of Chimay’s best ale, is a reduction of Agata & Valentina’s veal broth from one quart to two-thirds of a cup. And yet, when I took the casserole out of the oven, the sauce was still pretty runny. As I prefer creamy sauces, I may adulterate the dish by thickening the liquid with a roux. At the same time, my dreams of the soup involve at least the thickening of cream, so perhaps I had better leave the carbonnade alone.

I was supposed to buy two large onions along with the beef and the ale, but I forgot, and had to make do with the sorry-looking contents of the crisper. A tired Vidalia onion and a clutch of shallots. When I was through slicing everything, I had discarded nearly half. But it was enough.

The other night, we had Tetrazzini leftovers. I made the dish, comprised of chicken breast, velouté sauce, and spaghetti, two weeks ago. I dished it out into four of those lion’s head ramekins that are perfect for serving Hollandaise. I topped two of the ramekins with Parmesan cheese and warmed them in a hot oven. I covered the other two with plastic wrap and found room for them in the freezer. They made excellent leftovers. I worried that at least some of the spaghetti would turn into wires, but that did not happen. Again, I made the velouté with a severe reduction of chicken stock, which made the dish rich in every way. Kathleen couldn’t quite finish off her ramekin.

***

Tomorrow is New Year’s Eve, and Kathleen and I plan to observe it in the usual way, with champagne, caviar, and Radio Days. We’ve been watching Woody Allen’s valentine to the New York of his childhood on the last day of the year for two decades at least, and many of its lines are staples in our household macaroni. “Who is Pearl Harbor?” “You speak the truth, my faithful Indian companion.” “Hawk, the lions raw, is it the kingue approaching?” “I can’t take that much liquid.” “That’s no fluke!” Not to mention getting Regular with Relax. We even put up with the bathetic episode, right before the split, bittersweet finale, about the little girl in the well, because the montage, so to speak, of Americans of all walks united by the centrality of listening to the radio is so arrestingly beautiful, and at the same time testimony to an utterly lost world. Nobody listens today because everyone is too busy talking.

If we can manage to stay up, we shall speak to Will not just on his birthday but at the anniversary of his birth moment, 1:45 AM. It will be 10:45 PM in San Francisco, late for most six year-olds but not for Will, who has always been a night person.

***

Thursday 31st New Year’s Eve

Last night’s dinner went well. The beef was overcooked, but the sauce was delicious, and the soup was a keeper. Our friends brought a very tasty apple-cream pie. After dinner, we sat in the living room and talked until midnight.

The wives, high-school classmates, sat together on a love seat and chatted. The husbands sprawled, each on his own love seat, and argued. We argued about the failure of evolution to keep up with social and technological change. We argued about medieval science, which my friend believed to be a matter of church doctrine instead of scientific investigation. Our voices rising, we argued about universal franchise and the Voting Rights Act. Finally, even more heatedly, we argued about the Cold War. My friend asserted — without, I could tell, expecting to be contradicted — that the Cold War was not only successful but necessary, in preventing the spread of Communism around the world. Kathleen announced that it was time to go to bed.

I didn’t realize until later, after I’d loaded the dishwasher and Kathleen had gone to sleep, how far I have traveled from received wisdom on these as on so many other topics. I was appalled to surmise that a quick summary of my “positions” on many issues would mark me as an utter reactionary. But my “positions” are merely observations, informed by the historical considerations that I am always revising, and the historical connections that I am always working out.

Evolution

It is one thing to examine prehistoric skeletons and to observe that we share ninety-odd percent our genetic makeup with chimpanzees. It is quite another to overlook the role of social evolution in human development. It is true that social catastrophe can undo many of the webs of support that suppress violence and other undesirable behaviors in normal times. But a reversion to some sort of natural setting, “the way we were” in, say, 175,000 BCE, has never really occurred. So far, no society has ever been “knocked back into the Stone Age” and persisted at that level. It may happen in the future — who can say? — but such a disaster would be unprecedented. And even the Stone Age is not to be confused with the State of Nature. Human society does not evolve backward. It can only be destroyed, which is quite different.

Medieval Science

Technology and science were not connected in the Middle Ages, any more than they had been in pre-Christian antiquity. Science was entirely a matter of theories, devised by philosophers and tested by other philosophers. Empirical observation played almost no role in these inquiries. Technologists (ie, cathedral architects) worked by trial and error. The roof of St Pierre de Beauvais, for example…

The origins of modern science do not lie in the overturning of church dogma. The overturning of church dogma was a consequence of modern science. The origins of modern science lie in medieval technology. I wrote about this in September, quoting a quotation:

Before men could evolve and apply the machine as a social phenomenon they had to become mechanics. (PG Walker)

Modern science began with the application of tools to scientific inquiry. One of its first manifestations was the pendulum clock, a collaborative effort dating from the 1650s.

Democracy in America

My friend agreed with me that the United States is a mess right now, but he wasn’t clear about why. In my view, he couldn’t be, because he doesn’t want to concede — and who does? — that universal franchise and the Voting Rights Act explain a great deal of our predicament.

We Americans like to believe that we have made amends for the things that the Founders got wrong, the most egregious being slavery. Instead, as I see it, Americans have substituted workarounds for atonement. This nation was framed, in 1789 (when the first presidential election was held), as a patrician republic. Voting was limited, in each of the new states except Pennsylvania, to landowners. This is to say that the Constitution’s function was thought to depend upon an educated, stakeholding electorate, with an interest in participating in local government and staying abreast of national affairs.

Universal male suffrage was a sales pitch for the new states in the Near West. The populism thus engendered, having spread to the original states, eventually flowered in the presidency of Andrew Jackson, whose face cannot be removed from the twenty-dollar bill fast enough for me. The patrician élites were encouraged by the Jacksonian persuasion to conceal their patrician façades in a masquerade of common-mannery. This led to élitist opportunism and the replacement of patrician élites by robber barons in the big-spender department.

The result was a permanent bifurcation of the free American population into two classes: Élite (wealthy or educated or connected to the wealthy or educated or all of the above) and ordinary. As we move further from 1945, the astonishing growth of the middle class during the decades of postwar prosperity seems increasingly that: astonishing, and likely neither to last nor to be repeated. When the wonder years were over, many in the middle class — professional people especially (doctors and lawyers) — settled among the élite. The rest of the middle class reverted to ordinary.

The élite in America today appear to be bent upon starving the ordinary American to death. That is the extent of current élitist interest in the common man. You’d think that something else that happened in 1789 has been forgotten.

Anybody who thinks that the problems created by slavery, particularly that of a large population of people immediately discernible as slaves or the descendants of slaves by the color of their skin (a problem unknown to slavery in antiquity), have been “solved” ought to be stripped of any and all academic diplomas.

With the abolition of slavery amended into the Constitution after the Civil War, the American workarounds went in the direction opposite to that of atonement. Keeping blacks separate was the unofficial work of Jim Crow. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 climaxed a long and arduous attempt to undo the discriminatory régime in the South. Unfortunately, it infected the ordinary class of Americans with a resentful fear. Now that blacks could not be kept in their place, or denied the right to vote, many white Americans no longer felt “safe,” in their homes, in their towns, or even in their country. There had always been lone rangers on the fringe of American life, but ordinary white America responded to the Voting Rights Act with an upsurge in antisocial, siege-mentality behavior: “Christian” academies and gated communities, the proliferation of firearms. Élite Americans, meanwhile, congratulated themselves on their high-minded legislative success, and refused to see that there was still a problem. I speak, of course, of those members of the élite who were not actively stoking the fears of the ordinary class.

“So,” my friend argued, “you would undo the Voting Rights Act, because most blacks aren’t members of the élite class to which the Framers sought to limit the franchise.” Or words to that effect.

I should do no such thing. As European convulsions from the Reformation to the Terror to the Holocaust demonstrate again and again, you can’t clean up messes by undoing their causes. You have to move on. But moving on is a lot smoother if you know where you have been — as indeed the Founders did, having just experienced the five-year fecklessness of American government under the Articles of Confederation. I don’t believe that anybody seriously considered petitioning King George to “take us back.”

The Cold War

This was going to be my only subject today. I’ve been reading a string of novels by John Le Carré, and they have brought the Cold War into focus — not just the spying (which David Cornwell has concluded was silly and pointless), but also the ideological battle. What this battle really consisted of was a pair of power centers’ barking at their underlings about the horrors of the opponent’s way of life.

After World War II, Russia, which had suffered more than any of its Allies by several orders of magnitude, sought, quite naturally in terms of its history, to surround itself with a defensive perimeter. Infusing this perimeter with Communist ideology was merely the surest way of securing the possession of Slavic Europe, Hungary, and the adjacent chunk of Germany (this last the region from which most eastward incursions into Polish and Czech territory originated). Despite having overthrown the Tsar and the plutocratic élite that controlled the country until World War I, Russia remained Russia, as indeed the vibrant stardom of Vladimir Putin, attended by flocks of Russian Orthodox clergymen, makes crystal clear. President Putin is currently engaged in restoring the former Russian Empire, which was for seven decades known as the Soviet Union of Socialist Republics.

My friend evoked the Soviet embrace of Cuba. Was not the Cold War required to limit such “expansion” to that island? Explaining at length why my answer was a resounding “No” would be wearisome for reader and writer alike. Suffice it to say two things: Russia wished to counter the American military appanage of Europe with a pied-à-terre ninety miles from Florida. The Cold War had little to do with the thwarting of this ambition. It was on the brink of a very Hot War that the world trembled in October 1962. As for Cuba’s embrace of Communism, it was inspired by much the same degrading inequality that provoked the Russian Revolution.

That’s to say that Communism in Cuba was never a rejection of Capitalism. Something much older and meaner than capitalism prevailed in pre-Castro Cuba, a blend of the American plantocracy and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Cuban capitalists (or industrialists) were mostly rentiers, not what we would call businessmen. Too many Cubans were trapped in the backbreaking production of sugar.

Communism has the advantage of being a well-articulated ideology. Capitalism, in contrast, means many things to many people. In today’s Times, Jon Caramanica writes about shopping as a way to relieve trauma: “This is one of capitalism’s many tricks, and one of its best: the notion that you might rewrite your emotional life via acquisition.” Capitalism? How about consumerism? What prevented consumerism from thriving in Warsaw Pact nations was state control of industry, which is not the opposite of capitalism. Today’s China is conducting an exciting, sometimes too-exciting experiment in authoritarian capitalism, officially “communist” but wise to the fact that markets lead, instead of following, economies.

The Cold War was less about economic theories than it was about power structures. The Authoritarians fought the Liberals. The Authoritarians’ eventual defeat did not herald the victory of Liberals, however, mistaken as the Liberals might have been about that at the time. The Authoritarians are back, everywhere, with a vengeance. Quite a few of them are Libertarians and other oxyMoronic followers of Ayn Rand. Liberals have lost academia, traditional the Liberal nursery, to the Authoritarians who enforce political correctness. Let us not forget the Higher Authoritarians who would institute a theocracy. And this is just in the United States.

The Cold War was, ultimately, a very expensive organizing principle. You knew where you stood, even you doubted your next-door neighbor. All other hostilities were either limited or suppressed by Cold War strategies. When the Cold War came to an end, the economic boom was echoed by political collapse.

Because Liberals are helplessly élitist. I’m one; if you’re reading this, you probably are, too. We are certain that peace would reign everywhere if only everyone could see things as we see them. But we see things with minds that have been overhauled by liberal education and reassuring affluence. We may understand that very few people, essentially nobody, can see things as we see them without those benefits. But not only have we failed to generate the economic wherewithal to spread those benefits — we haven’t learned how to domesticate wealth, how to make it appear where and when we want it to appear; we have also lost the art of persuading others that they are benefits.

I’m R J Keefe, and I’m a member of the liberal élite. And, notwithstanding all the many mistakes made by this group, proud of it. I believe that we are still humanity’s best hope for continuation on Planet Earth. That is why I am its scourge.

Happy New Year!