Gotham DiaryTK:

A Day at the Office

2 July 2015

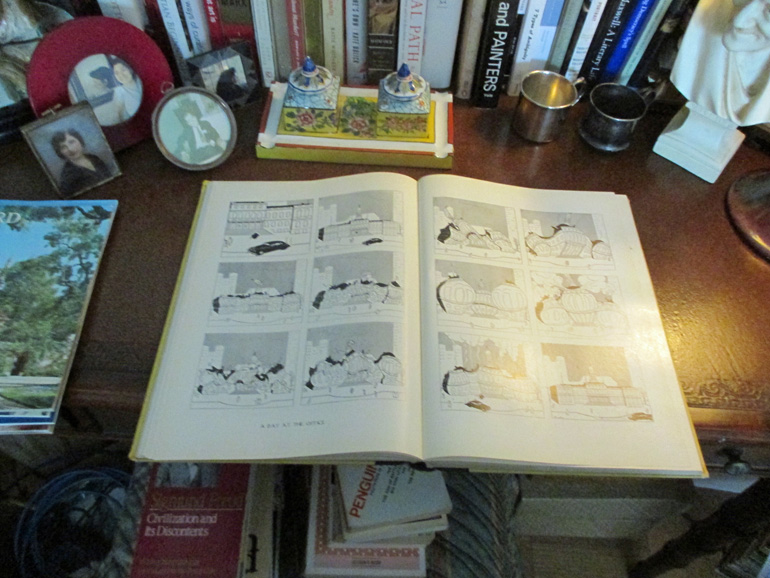

For a few days, I’ve been gazing every now and then on the twelve-panel drawing from an old New Yorker, collected in the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Album, one of the books that introduced me to my life. The black-and-white sparkle of the panels suggests Gardner Rea or Gluyas Williams, two exponents of the elegant, understated aesthetic developed for the magazine by Rea Irvin, the creator of Eustace Tilley. This cartoon, “A Day at the Office,” is signed “Frueh,” presumably Alfred Frueh, another artist of the early days. I took a photo just now to serve as a thumbnail: to appreciate it fully, you’ll have to find a better copy.

The panels relate a simple narrative. A limousine pulls up in front of a handsome, neoclassical building — New York’s City Hall, in fact, one of its loveliest buildings but not, I think, a widely known one. Frueh takes pains to capture the building’s rectilinear grace, as if he were preparing an architectural rendering for a client. This is not mere diligence: it frames the glorious silliness to follow. No sooner does the little man who gets out of the limousine and climbs the steps to the main door enter the building than it begins to convulse. First, it deflates, as if beset by an identity crisis. The cupola lists at a 45º angle; the pillars of the portico are entwined in confusion. Soon, City Hall is devoid of straight lines. Then, after lunch presumably, the building suffers the opposite distortion. It begins to swell like a balloon. First the central block lurches upward, then the wings. Then the eaves lift like flaps, emitting gusts of steam that suggest an imminent explosion. Finally, as the little man emerges, City Hall relaxes. As the limousine pulls away, it stands restored to it beaux-arts rectitude — only to await the same ordeal tomorrow.

I’d love to know how I came to understand what this cartoon is about. Who is the little man? Did I grasp it all at once, because someone explained it to me? Or did I put it together slowly, as I put so many things together in that factitious suburb where I grew up? I’m sure that I liked the cartoon enormously even without being in on the joke. A lot of the joke is, after all, explicit. With the help of the caption, it’s fairly clear that the building symbolizes “business as usual,” and that the little man is a force for disruption. This disruption, represented by contortions that no real building could survive, is great fun to watch — slapstick, really. But the sliest part of the joke is that the disruption is temporary.

I can’t believe that I always recognized City Hall — but it’s just possible. I’m sure that I had to be told that the little man was Fiorello LaGuardia, New York’s mayor from 1934 to 1945, and arguably the most progressive man ever to lead the city. Half-Italian, half-Jewish, he represented the city’s population, not its élite. He talked with his hands. He threw tantrums. He was even — a Republican! I would have known the name from fairly early on, thanks not only to the airport but also to a musical, Fiorello!, that ran for a while.

It is a truism of humane architecture that our sense of possibility is shaped by the structures that we inhabit. Frueh’s drawing is a daydream about the converse. What if the possibilities of structures were shaped by the human beings inhabiting them — in this case, presiding over what went on inside? What would happen if a civic monument to modest affluence got roaring drunk? (As Frank Gehry’s creations suggest to me, these meditations are best conducted in two dimensions.) What makes “A Day at the Office” sublime is the detail with which Frueh follows the upheaval. He draws it all in the painstaking manner of the first panel. None of the architectural details registered at the start is neglected, and each is recognizable even at its most twisted. I could not possibly pick a funniest.

The exuberance of Frueh’s drawing does not obscure the elegance of the compositional scheme, even if awareness remains subliminal. The outer pairs of drawings show LaGuardia coming and going. This leaves two inner quartets, the first collapsing, the second bursting. There is nothing chaotic about this presentation of chaos. However bewildering the experience is for poor old City Hall, the viewer enjoys a completely satisfying day at the office.

***

A long time ago, Robert Benchley wrote a parody of a scientific news report entitled, “What Is Humor — a Joke?” When I read this piece for the first time, in tenth grade homeroom at Bronxville High School, I had to be asked to stop laughing. I wasn’t just laughing. I was almost as crumpled as Alfred Frueh’s City Hall. I had to close the book, lean over the desk, and gasp for air. Tears blinded my eyes and gummed my cheeks. To say that I created a disturbance is an understatement: I was an irresistible and annoying center of attention. It wasn’t that Benchley was so funny. It was that I’d had no idea that such funniness existed. It was really quite like the surprise of my first sexual encounter. But even greater, because I had heard that sex was a big deal. I hadn’t heard that about laughter. I didn’t know that laughter could open the door to a new physical experience — a new dimension, to use a cliché popular at the time. I can still remember the shock of Benchley’s ridiculously-named “Mergenthaler Laugh Detector.” My storm of laughter was the relief of a very serious person who has just been assured that institutional pomposity need not be taken seriously — indeed, that it ought not. There was a thick seam of Allez, courage! in Benchley’s “joke.”

The essay is no longer very funny. I don’t even find it amusing. Benchley’s style is too scattershot. Whether this is because he was a drunk or a depressive doesn’t matter; for one reason or another, he surrendered to a stylistic opportunism that put equal weight on very unequal gags. And a great deal of the humor is dated, because society has changed, and has been in no small part changed by old jokes. The society dragons that Margaret Dumont played for the Marx Brothers no longer exist — not in the United States, anyway. We laugh at her as a clown, not as the representative of a class of rich widows. Humor is an awfully delicate thing, even in the life of one person. That so many cartoons in the Twenty-fifth Anniversary Album are still so funny — but are they? Are they still funny to teenagers who open the book for the first time? I don’t mean to teenagers at large, but to the thin band of clever young people like the boy I used to be. Can “A Day at the Office” still make anyone under twenty laugh?

I hope so.

Bon weekend de fête à tous!