Gotham Diary:

Free Company

12 December 2014

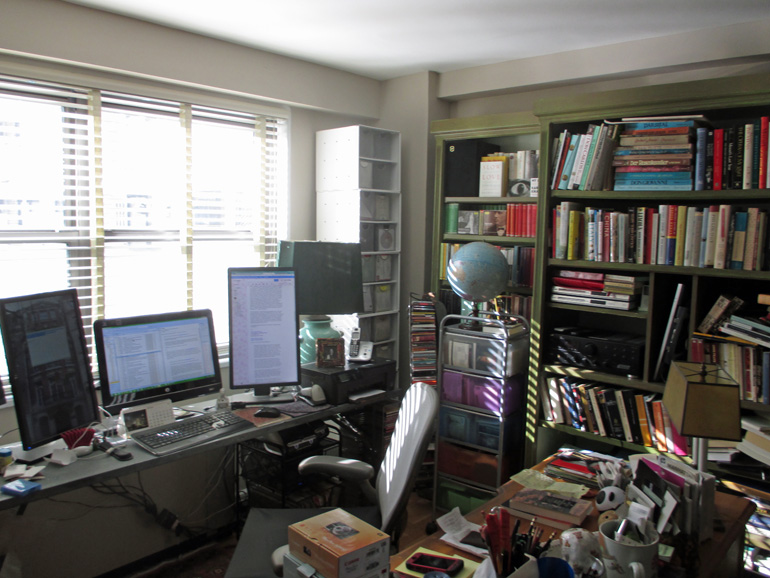

A few weeks ago, I placed a photograph of the book room taken from this angle at the bottom of an entry. I had the idea of posting an image each Friday, to show how the moving in was coming along. The following Friday, however, was the day on which Fossil Darling and Ray Soleil did something special, and I was distracted. Ray had already applied a coat of paint, mixed with glaze, to the bookcases. One coat. That was all it took. With sunlight streaming into the room, you can tell that one bookcase used to be bright green, while the other two were dark blue, but you have to be looking for this. A casual glance suggests that all the bookcases are a bronze brown. I was never so impressed in my life. One coat!

This photograph nicely fails to suggest the extent of disorder on the bookshelves, but there are plenty of hints. Perhaps in another three weeks I’ll post another photograph. Perhaps not — I’ll be in San Francisco. (Yikes.)

***

David Brooks’s column in today’s Times has fallen into my lap. “In Praise of Small Miracles” retails anecdotes about how behavioral economics is being used to make life less awful for people around the world. In Kenya, iron boxes encourage savings, and heckling bad drivers reduces automobile casualties. Sugar cane farmers in India are invited to make important decisions (about choice of fertilizer and schools) after they receive their annual payment, not before, when they tend to score ten points lower on IQ tests. Bonuses are awarded to teachers on the understanding that they must be returned if quotas are not met. The gist of all these stories is the importance of understanding that we are generally far more motivated to avoid some things than we are to achieve some others, and I don’t think I could find a more eloquent expression of the little formula that I inserted into an entry the other day (less awful ≠ more better). It’s a mistake to try to work with a scale that ranges from bad things to good things, because the two are not continuous in our minds. It’s a mistake to exhort people to do good things so that bad things won’t happen, because we think about good things and bad things with different parts of our minds. If you want to focus on making bad things less bad, it’s better not to muddle the picture with talk of improvement. It’s enough to show ways in which bad things can be made less awful. And this is something that institutions of all sizes can do.

Does this mean that human engineering works? No. Human engineering envisions improved human beings. Behavioral economics is more modest. It doesn’t seek to straighten the crooked timber of humanity, but only to accept it — to work with its grain instead of against it. Brooks’s small miracles are no more (and no less) miraculous than raising a happy child. What’s new is the understanding that informed, humanist concern for the welfare of others is the first principle of social policy, just as it is of successful parenting.

It’s because of this focus on safety and soundness — making life as little awful as possible — that parents and institutions do best to leave the positive pursuit of happiness to others, to contributions of the individual’s peers — to colleagues, neighbors, friends, and lovers.

The parent who has created a safe and loving environment has done enough. It’s a mistake to proceed to fill up a child’s life with extracurricular activities. Similarly, it is useless for universities to pay any attention whatsoever to those extracurricular activities when deciding which applicants to admit. Parents and schools are charged not with turning out well-rounded adults but with seeing to it that adults are not ill-equipped to live in the world — in the same way that they are not malnourished or unclothed. It is the responsibility of parents and schools to teach young people the conventions of social intercourse and the principles of political government. It is the generosity of teachers and lovers that inspires our lives with the visions of happiness that make the hard work and mortal failing of life more than worth the trouble. We pursue happiness in the free company of peers.

(Teachers as peers? I’m using “teacher” in a special sense, the one that marks our recollection of teachers who “made a difference” to us. The difference made in such cases is an understanding of the world, and it is not taught but delivered, by one mind to another. When this “difference” is being “made,” the teacher is, momentarily, not an authority figure, but a guide, as Virgil was to Dante.)

***

Coming home from the Remicade infusion yesterday, I finally got to sit in one of the new taxis with a sunroof. It was a great treat, even in the dark. As we drove up First Avenue, I watched as the tops of tall buildings floated by. I can never see anything much from the sedan windows of a taxi, and I can’t see much more when I’m walking; to glimpse the top of a building across the street, I might very well have to stretch out on the sidewalk. The view through the sunroof of so many lighted apartments reminded me forcibly that I live in a very big city full of a lot of people. That this immense population is neither crowded nor oppressive amazes me. (NB: If you are reading this close upon a return from the Fairway in my neighborhood, please give the sentence fifteen minutes of deep breathing to achieve plausibility.) All those rooms, stacked in columns twenty or thirty tall, each kitted out differently, each trailing a unique bundle of stories. Comparisons to anthills would be blind and stupid.

And then we pulled into the driveway of my building. I am already beginning to forget how long we couldn’t use it.

Bon weekend à tous!