Gotham Diary:

Morning Drift

21 February 2013

Kathleen had to be out of the house early this morning, so there would be no lingering over tea and toast. I woke up when she did, but lazed in bed, drifting in and out of states of mind, some of which were dreams. It was pleasant; I wasn’t exhausted. The morning before, I was so tired that I was afraid to face the day ahead, even though the calendar was perfectly blank. This morning, even as I dozed, I was fine with knowing that that I’d be up and about presently.

And yet, one of my first thoughts was about a good death, which I felt I was previewing, lying there in comfort. I do hope for a good death, and dread a bad one. I hope to die before the collapse of civilization that so many imaginative people these days enjoy foretelling. I am not particularly anxious that this will occur anytime soon, and I know that, meteors aside, it is very unlikely to occur as a global catastrophe. But I want no part of it, am not curious about it at all. It’s an unhealthy subject, really. I probably wouldn’t be going to see the new production of Parsifal anyway — I seem to have attained a measure of Gelassenheit about sitting through plays and concerts — but when I heard that it is set in “postapocalyptic times,” I was relieved to put it out of mind. Doomsayers are bad for morale.

Why doesn’t the word “sophology” exist, I wondered? I ran a mental finger over the bruise left by Arthur Danto’s book about art. Philosophy is the love of wisdom. Although philosophers have certainly gone in for rigorous-looking syllogisms and categories, and bristled with metaphysical lingo that frightens off the uninitiated, this love-of-wisdom does seem aptly named: it’s a pleasant pastime really. Sophology would be quite different. The study of wisdom: what would that look like? I think that it would look like Hume and James. No grand systems for them! Their wisdom begins and ends in deep humility. I would say that today’s cognitive revolution is sophologic. I would also say that I haven’t read Hume in forty years or more. Not another word out of me on this topic until I’ve done a bit of re-reading.

The other day, I pulled down a book that I thought I should re-read, Maurice Keen’s Chivalry, but it didn’t take long to doubt that I had actually read it before. If I did read it, then I’m guilty of having appropriated its contents and marked them, mentally, as my own original thinking, because as I turn the pages, I say yes, in that deep way that’s provoked by books that chime with ideas that we’ve arrived at, if so very well articulated, on our own, but that we don’t feel we’ve encountered elsewhere. There are two phenomena that suggest to me that I really haven’t read Chivalry before. I haven’t felt the low vibration of familiarity — which has nothing to do with “content” but rather registers the odd turn of phrase, the peculiar anecdote that sticks in the mind — that signals the forgotten book. And the chiming isn’t entirely harmonious. Keen and I are both extremely interested in the relation between knighthood and Christianity. Chivalry — the first half of it, anyway — assiduously traces the ultimate failure of Church leaders to interpose ecclesiastical authority into the creation of knights. My own interest takes a slightly different course: aristocratic families in Western Europe completely subverted Christianity when they saw that there was money in it, so that the “Christianity” of the knights was not much more authentic than the “christianism” on show at one of today’s mega-churches. Keen mentions here and there that Church leaders generally came from knightly families (at a minimum), but he does not really grasp that what those leaders were after was control, not reformation.  The “three orders” writings of Adalbert of Laon and Gerard of Cambrai, dating from the early Eleventh Century, were well-received precisely because they formalized a social arrangement that was already firmly in place. There were those who prayed, those who fought (“protected”), and those who worked — to feed the first two. There may have been three orders, but there were two classes.

(Only two classes. The “waning of the middle ages” began when a new, third class — a wealthy and powerful bourgeoisie — arose at the end of the Fourteenth Century, and there was nowhere, conceptually, to put it.)  Â

Then I had a dream. I nodded off and made a fool of myself. I bought a large orchid plant and took it to Crawford Doyle, obviously thinking to ingratiate myself in some way, or, better, to become more than just a good customer. Special! Just as obviously, I saw, as I carried the plant into the shop, how inappropriate this was. I made up a story, which neither Dot nor Lauren believed for a second (I could tell!) about having been given an “extra” orchid by a “cousin” — thus transforming my gift into refuse! Humiliation was complete when I slipped out of a shoe and saw that we were now in “my room,” the floor of which was littered with loafers and moccasins. For the last moments of the dream, I got to savor being hopeless at eighteen.

***

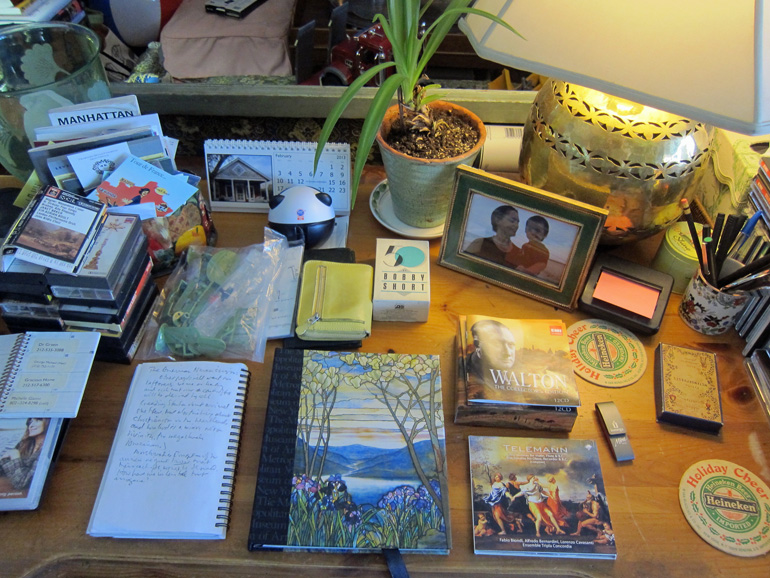

I don’t know what’s in store for today; it’s uncertain whether I’ll help out with Will’s winter break today or tomorrow. Tomorrow would be great; I will really be rested up by then. If so, I’ll deal with the too-many piles on my writing table. Â