Gotham Diary:

Where to Find My Library

10 January 2013

The last essay in James Wood’s new collection, The Fun Stuff, concerns his late father-in-law’s library, which it fell to his charge to pack. I read the essay with bulging interest, as the disposal of my library is much on my mind these days. It’s not that the end seems nigh. What has dawned is the realization that nobody will be interested in possessing my collection of books as such. It will be as individual volumes that the books dissolve into the used-book universe. I am learning not to regret this, learning, that is, what my library really is, and where it actually exists.

Two of Wood’s anecdotes — neither about his father-in-law — stuck with me when I put the book down. One of them I had heard before. It was something that happened to Frank Kermode when, toward the end of his life, he moved house, and the boxes of books that he wished to keep were mistaken, on the sidewalk, for rubbish, and carted away, leaving him “with a great deal of literary theory,” Wood writes.

The story once seemed horrifying to me, and now seems almost wonderful. To be abruptly lightened like that, so that one’s descendants might not be lingeringly burdened!

It still seems horrifying to me, because poor Kermode was still alive. The other anecdote presents Susan Sontag in a now=familiar blaze of insecurity. I won’t repeat it entire; here’s the end:

… and it seemed strange of her not to comprehend what I intended to say, which was simply that, like her essays [Sontag’s point], her library was also more intelligent than she was.

I understand what Wood means to say here, but I would put it differently, probably because his essay sparked my mind on to what I think is a better grasp of the matter. I would say that anyone’s collection of books is more intelligent than its owner. But I would insist that the library itself, the library within that collection, is centered in the mind the person who has read the books in it, and held on to a memory as well as to the book.

That is why my library will not survive me, even if someone begs to take the whole lot, even if someone goes so far as to replicate the blue room in a museum. To anyone but myself, the collection will be just that, books on a shelf. What binds those books into a library is the web of connections in my head, some of them quite conscious, others all but unavailable. This had already been intimated to me by the work that I’ve been doing on culling the books, but I lacked the manner of expressing it.

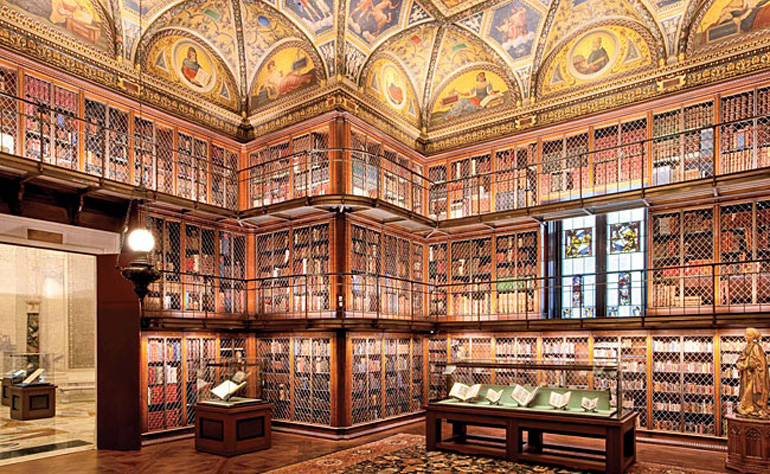

My misgivings about personal libraries were awakened several years ago by a visit to the Morgan Library and Museum. In the grandiose library, I was peering at the spines through the grilles. It was all rubbish. Old travel books, I recall, or old translations of things. The books might have been valuable as objects, but their contents would be of no interest to anyone but a scholar, and, as such, ought to be uploaded into the clouds for permanent and universal access. It is not a library at all, but a collection put together for the greater glory of J P Morgan. It is hard to imagine him reading much of it. To put it another way, I should like to know of what books Morgan’s true library consisted. That would be interesting to know. (I do hope to leave behind a book list!) The library itself, however, died with Morgan. Â

***

Scouting the Internet for reviews of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, I felt a bit foolish getting so excited by a book that came out last spring. I know why I shouldn’t have read it then. I was in the depth of my English commitment, reading one Elizabeth Taylor after another, and then, as i recall, reading and rereading Alan Hollingshurst. I was also loosening the compulsion to read all the new reviews. The mere appearance of “halftime” in a book’s title would have steered me away.

I don’t think that you’ll find me compiling ten-best-of-the-year lists of anything, but I have to say that it was the way Ben Fountain’s novel kept coming up on other people’s lists that concentrated my attention. The decisive pointer was Laura Miller’s rather harsh list of five books that she couldn’t pick up or get through. One of them was Kevin Powers’s The Yellow Birds, the “other” Iraq novel of 2012. Miller compared it unfavorably to Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. The buzz had piled up in my mind. That, too, was part of my library; it still is. And, now that I’ve written it down, what is it? An annotation to my book list, I suppose.