Gotham Diary:

The Prince Trilling

14 January 2012

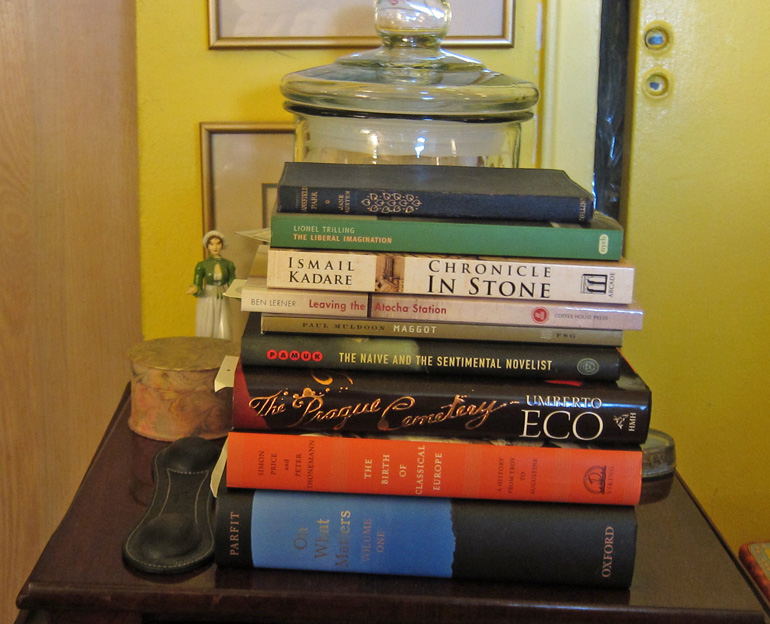

Resisting the newspaper, I picked up The Liberal Imagination and read the essay about The Princess Casamassima, Henry James’s novel of the late 1880s. I’ve read the novel twice, but not recently. Let me be the first to admit to the seductiveness of its title, which shows James at his worldliest. The title turns out to be hugely ironic, but you don’t know that when you pick it up the first time. Princess Casamassima would have been grand enough — what name could suggest a vaster palace? But by inserting the definite article, James raises the wonder higher, and puts the lady on a level with the Sun King. In the way of titles, that is. You want to know more.

But all I ever remember of The Princess Casamassima, aside from a blurred sense of cockney settings that aren’t, after all, the sort of thing that draws me to Henry James, is the lush description of Medley, the old house in which the tragic hero, Hyacinth Robinson, has his first taste of the “country.” The house ” was richly gray wherever it was not green with ivy and other dense creepers” — it almost seems a natural feature of the landscape. Which is of course the whole point of the very exclusive “country” that could be found here and there in the English countryside. I can’t think of another passage in James that so particularly identifies the features of a house, but then it is not usual, in James, to view architecture through the eyes of a poor young man who has never been far from London.

How appealing would the more apt title, Hyacinth Robinson, be? I have to say that “Hyacinth” sets off a cognitive muddle. It’s so fancy! Sure, the hero’s mother was a French maid. But it’s hard to imagine anyone at any social level making it through twelve years of English life with the burden of such a name. The name is also as ironic as the title: our Hyacinth is a not very floral terrorist. And “Robinson” drags in Defoe. I would have to be paid, a lot, to read Hyacinth Robinson. But I’ve read The Princess Casamassima, as I’ve said, twice, for free. Now I’m wondering if I’m in for a third visit.

Trilling’s essay is impassioned by an almost lawyerly zeal to defend a novel from Henry James’s least popular period, the middle. Between Washington Square, The American, and Portrait of a Lady at one end of his career, and the trio of thrillingly dense novels the closes it, there range a baker’s half dozen of books that only James fans and academics bother to read. It’s not that they’re bad novels, but they’re inferior as books by Henry James to the degree that they are less dramatically focused than the early works and less dazzlingly complicated than the later ones. But Trilling isn’t trying to make a case for The Princess Casamassima as “great” James. On the contrary, he locates it in the tradition of “great” European novels that runs from Le rouge et le noir through The Idiot. He describes the type as “the young man from the provinces” novel. A poor young man is wafted by chance into the precincts of wealth and power, and at the very least suffers almost fatal disillusionment.

It isn’t by virtue of being such a novel that The Princess Casamassima strikes for Trilling the note of true greatness, however. It is the book’s “moral realism” that makes it “an incomparable representation of the spiritual circumstances of our civilization.” That’s what Trilling says. Looking over his shoulder, I wonder if it isn’t the way that James applies his moral realism to the political circumstances of his story that excites Trilling. The easiest way to describe The Princess Casamassima to someone who is otherwise well-read would be to compare it to Conrad’s The Secret Agent and Under Western Eyes. These are stories about anarchist conspiracies and assassination plots, and they were much on people’s minds toward the end of the Nneteenth Century. In the Twentieth, they would flower balefully in the crushing dictatorships that brought the world to a second hot war in the 1940s and then to a cold one, at the very beginning of which Trilling was arduously assessing the legitimacy of liberal opposition to communism. That what the following extraordinary passage is all about:

It is easy enough, by certain assumptions, to condemn Hyacinth and even to call him names. But first we must see what his position really means and what heroism there is in it. Hyacinth recognizes that few people wish to admit, that civilization has a price, and a high one. Civilizations differ from one another in what theygive up as in what they acquire; but all civilizations are alike in that they renounce something for something else. We do right to protest this in any given case that comes under our notice and we do right to get as much as possible for as little as possible, but we can never get everything for nothing. Nor, indeed, do we imagine that we can. Thus, to stay within the present context, every known theory of popular revoltuion gives up the vision of the world “raised to the richest and noblest expression.” To achieve the ideal of widespread security, popular revolutionary theory condemns the ideal of adventurous experience. It tries to avoid doing this explicitly and it even, although seldom convincingly, denies that it does it at all. But all the insincts and necessities of radical democracy are dagainst the superbness and arbitrariness which often mark great spirits. It is sometimes said in the interests of an ideal or abstract completeness that the choice need not be made, that secuirty can be imagined to go with richness and nobility of expression. But we have not seen it in the past and nobodoy really strives to imagine it in the future. Hyacinth’s choice is made under the pressure of the counterchoice made by Paul and the Princess; their “general rectification” implies a civilization from wich the idea of life raised to the richest and noblest expression will quite vanish.

We may not need The Princess Casamassima now quite as much as Lionel Trilling did sixty-odd years ago (when the novel itself was sixty-odd years old), but we certainly need Trilling’s insistence on the kind of “superbness and arbitrariness” for which a liberal society ought to make sacrifices, and without which the superiority and aloofness of mere wealth are empty evils.