Gotham Diary:

Bulletins

Tuesday, 29 July 2011

My latest problem is: Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletins. These quarterly publications pile up! I’ve got nearly a foot of them. That’s a lot of shelf space, if you’re wondering. And I don’t have it. Not for the Bulletins.

Aside from the occasional issue devoted to recent acquisitions, each quarterly bulletin is devoted to one theme: the art of a region, a period, or even of one particular artist. Occasionally, the Museum resorts to bulletin format for minor catalogues, as was the case when Vermeer’s Milkmaid paid a visit from the Rijksmuseum. The format blends light-handed scholarship with texts that the educated general reader will find informative and well-written. But I have yet to encounter a Bulletin that tells me everything I want to know about work that already interests me, and Ican think of only one instance when a Bulletin sent me to a part of the Museum that I’d never been to before in search of works that I hadn’t thought I’d care much about. I ought to read the Bulletins as they come in; that goes without saying. But it would take eight to ten people to get through the stuff that I ought to read. At my pace, anyway.Â

So they pile up, unread for the most part. Here, from Summer 2001: Ars Vitraria: Glass in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I don’t know quite how to approach it. It looks like a high-end catalogue of gifts that happen not to be for sale, but there are a few stained-glass windows that have nothin,g beyond their common material, to do with anything else in the book. One of the windows comes from Rouen Cathedral (!) “Theodosius Arrives at Ephesus (Scene from the Legend of the Seven Sleepers),” it’s called. The accompanying passage provides dates for Emperor Theodosius II (a long reign, 408-50) and recites the legend (the sleepers were persecuted Christians who had been tucked into a comfy cave in the Third Century, miraculously resurrected). We’re also told that the panels, of which this is just one, were dismantled and rearranged in the Rayonnant style to fit the lancet windows of side-chapels that were added to the cathedral, presumably in a way that blocked off (or opened up) the panels’ original windows. As a result, the original composition “of cluster medallions against a mosaic ground, like the contemporary windows at Chartres,” has been lost. Very interesting!

In most cases, if I want to see an item that’s written up in the Bulletin, and it belongs to the Museum, I have only to walk down the street, but a glance at Theodosius arriving in Ephesus will require a trip uptown to the Cloisters. By the time I make my next trip, I wonder what I’ll still recall of the information in the foregoing sentences. I’m not an aficionado of stained glass, but I have an abiding interest in Medieval art, so it’s not a waste of time for me to know a little something about this fragment. Nothing in the world, however, is going to make me want to know more about the pair of Syrian blown goblets from the Eleventh Century that, to my eyes, are the one thing that glass ought never to be: dirty-looking. Â

Here’s a good one. Summer 2004: “The Flowering of the French Renaissance.” I open up to a handsome chalk drawing of a young man from the middle of the Sixteenth Century, attributed to the Clouet studio, who may be Guy de Laval XVII (who died at 26 in 1547) or Guy XVIII. It belonged to Catherine de’ Medici. “Skilled in diplomacy and in arranging marriages for her children, Catherine was eager to identify noble men and women throughout Europe.” Well, you could say that about her, I suppose, but it would sound better if she’d left a few grandchildren, and hadn’t acquired such a toxic reputation among Protestants. Not that I’m complaining! Page 23 of this bulletin features an image of one of my all-time favorite weird pictures, Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh: An Allegory of the Dinteville Family, by an unknown artist. It hangs, these days, over some furniture somewhere, but it used to be found in the galleries that you’d exit into after seeing a special exhibit in the Old Master Galleries (that’s what I call them). It’s bold and clear (as clear as a Lotto), and homoerotic in a way that manages to be both robust and coy. It’s very naughty, as befits a painting about a family scandal. On page 35, however, there’s a photograph of a set of deluxe pruning tools. More items that aren’t for sale.Â

I don’t think that I’ve ever opened Summer 2009 before today. They don’t put the titles on the cover. You have to open them to find out what the subject is, if the cover art doesn’t tell you. The cover art here doesn’t tell you, and you probably wouldn’t figure it out, either — so I’ll let that go. The issue is devoted to “Scientific Research in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Now, it’s clear that we all ought to read this from cover to cover. I’m serious! You should see some of the equipment they’ve got there. Caption: “71. (left) Pendant (fig 65) being placed into the chamber of a scanning electron microscope (SEM) for surface analysis of enamels.” Is that contraption really sitting somewhere in the basement at 1000 Fifth Avenue? On page 41, a chart entitled Marker, showing a schematic Antibody brushing up against a schematic Antigen. This is from “Immunology and Art: Using Antibody-based Techniques to Identify Proteins and Gums in Binding Media and Adhesives.” I expect that a learned version of this paper has been published, eye-glazingly, elsewhere, but it’s stuff like this that keeps me in shape as a know-it-all. With just a few bits and pieces gummed and bound to my conversational palette, I can paralyze up five cocktail-party guests at close range.Â

Ooh, Madame X. Here’s one I’m never going to throw away: Spring 2000, “John Singer Sargent in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” An all-time beloved picture: Mr and Mrs I N Phelps Stokes. The thing to remember is that ‘P’ comes before ‘S.’ I’m just thinking out loud, here. If I were a real knickerbocker, I’d know that it’s “Phelps Stokes” and not “Stokes Phelps,” but every time I mention this picture I wonder if I’ve got it right, and hesitate so long that it sounds like I don’t know what I’m talking about. The Phelps Stokeses had houses on the same block of Madison Avenue as the Morgan house that’s now part of the Morgan Library; it may even have belonged to them at one point. I remember reading that somewhere. Also that Mrs Phelps Stokes, the wonderful Katharine-Hepburn-like American beauty in Sargent’s picture, died more or less broke in the Fifth Avenue apartment building built by her antiquarian husband. The Crash, you know. He’s in the picture, apparently, because he showed up at the studio instead of his wife’s wolfhound. Is that true? Almost. From page 28: “…. and the dog was unavailable — Stokes had ‘a sudden inspiration,’ he recalled, and ‘offered to assume the role of the Great Dane in the picture. Sargent was delighted, and accepted the proposal at once…'” You can’t make this stuff up. (Although evidently you can mangle the details.)

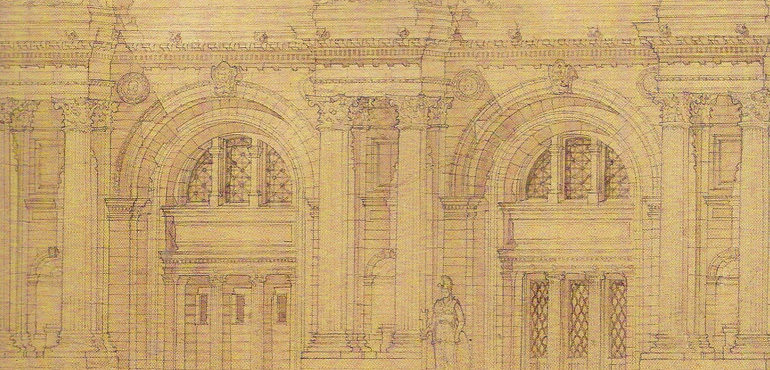

I don’t know what I’d do if I had to decide between the Sargent bulletin and Summer 1995, and could keep only one. Summer 1995 is devoted to the architectural history of — the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I have pored over every page with the enthusiasm of a fanatic child. Because what’s more interesting than almost any individual thing in the Museum is the building itself. I don’t mean beautiful; I mean interesting. To look at the aerial photograph of the Museum taken in 1920, before the lower reservoir was replaced by the Great Lawn, before the first bits of the American Wing were tacked on to the northwest corner, before — just what was tucked into that space before they built Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium (which was still new-ish when I first attended lectures there in the early Sixties)? — to look at this picture is to be confronted with a radically different Manhattan, a place familiar but incomplete, a town where they have no idea what’s coming. The most futuristic designers of Hollywood could never have imagined what would be added to this complex of structures in the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties. That’s because no one would have foreseen changes in the nature of the Museum itself. No one in 1920 could imagine the fun that my grandson would have running around the Engelhard Court — or the smiles on the guards’ faces.Â

Let’s do this again some time! Maybe I’ll come across a bulletin that I can deaccession.