Nano Note:

Playing Favorites

The other day, my daughter asked me if I’d like to have a box of classical-music CDs that she was getting rid of. Either she didn’t care for them or she had copied them into her iTunes library, but I was happy either way to take them home. When I went through the discs, I saw that I’d given some of them to her myself, years ago, and for pretty much the same reason that she was giving them back to me: a shortage of house room. (I certainly don’t have more storage space today, but by getting rid of jewel boxes I can store discs more compactly.) Most of my handovers were what I thought of as secondary recordings of beloved works, purchased for the CD library that I kept at the apartment at a time when I was spending most of my time at our house in Connecticut. When we sold the house, I no longer needed these extras, because I would invariably listen to my favorite recording of almost anything, given the chance. Of course there were things that I loved so much that I had multiple recordings. Mozart’s piano concertos, and his later operas (I have six Cosìs alone; seven if you include a DVD.) But I thought that it was enough to have just one recording of most pieces of music. My youthful impulse, not surprisingly, had been to have many different compositions in my library, and this necessarily limited the collecting of different performances of the same compositions. One set of Chopin’s Nocturnes was enough. I don’t think that there was anything unusual about this outlook.Â

There are two ways to hear classical music: you can select a recording and play it on some device or other; or, you can tune into the radio (more likely, its successors, XM and Pandora). You can choose what to hear yourself, or you can leave it to others. Leaving it to others is always easier, and unless you are sitting down to listen to a particular performance — and doing nothing else, except possibly following the score — it is something of a bother to take on the job of filling the air with music. What to play? The decision alone is laborious in its way, but the real work begins when you get out of your chair, paw through your library, find what you’re looking for, remove the LP or tape or CD from its sleeve, fiddle with the playback device (fiddling is inevitable; you have to put away whatever you were listening to before), and then go back to doing whatever you were doing. The burden of this effort and interruption is not very onerous, of course, but it’s onerous enough, especially with repetition, to steer you toward choosing what you think will be the best music to listen to; and, once you’ve picked the composition, an even stronger bias exerts itself in favor of the best recording that you’ve got of whatever music we’ve chosen. This is what makes those secondary recordings superfluous. If, whenever you want to hear Schubert’s Quintet, you’re going to choose the Alban Berg Quartet’s recording (even though you know you ought to give other performances a listen every now and then), why clutter your library with CDs that you’re never going to choose? That’s why I was glad to give my daughter the other one.

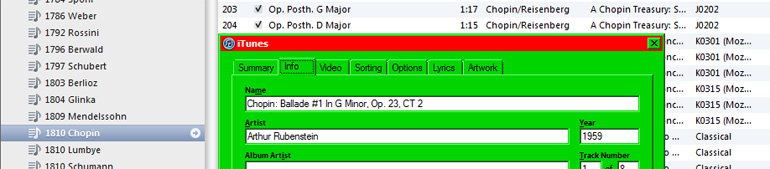

I had a favorite recording of Chopin’s Scherzos and Ballades (works that are often coupled on CD, as are the Schumann and Grieg piano concertos): Vladimir Ashkenazy’s. Well, perhaps it wasn’t my favorite recording, because it was my only one. I liked the music, but I didn’t know it well enough to appreciate different performances, so, following the law set forth above, I invariably chose what in fact was the only recording in my library. I wasn’t aware of doing any of this until I began to compose iTunes playlists. In the early days, two and three years ago, I’d stick in a scherzo or a ballade on a playlist the way that I’d have inserted it in an hour-long program at the radio station, to vary the tone and texture. At the station, I had several recordings to draw on, but with my iTunes playlists, it was always Ashkenazy’s recordings, and I was perfectly happy with that. I heard Chopin, not Ashkenazy. Until, one fine day, I came across a CD of the same music played by Arthur Rubinstein. I can’t remember why I bought it — undoubtedly it was in the interest of “giving other performances a listen every now and then.” That hadn’t happened; the Rubinstein CD mouldered among the RCAs. But for whatever reason, I copied the disc onto iTunes and used all of it in a playlist that I was putting together at the time.Â

If you stop to think that listening to a twelve-to-twenty hour playlist, weeks, months, or years after assembling it, is a lot like listening to the radio, especially with regard to cutting out the effort and interruption of choosing what to listen to piece by piece, CD by CD, the you’ll see where this is going. Not long after stocking the playlist with the Rubinstein Ballades and Scherzos, I was shocked by how different the familiar Chopin sounded. How much bolder and more youthful! Not that I prefer my Chopin to be bold and youthful; on the contrary, the Ashkenazy recording would still be my favorite. But here I was, listening to Arthur Rubinstein, without having made any effort to do so, and that was fine. A nice change! (It’s also worth noting that I was hearing each Scherzo and Ballade one at a time, spaced out over a playlist that lasted all day, and not all of them at once.) It wasn’t long before I took a new look at Bach in Order playlist.

I had thought, initially, that I would rotate performances within the one playlist. (At the time, I had two sets of Bach’s Cello Suites and several performances of the French Suites.) Now it occurred to me that it made more sense to have multiple playlists. I’ve just put in my order for the recordings that will fill out Bach in Order IV. To create Bach in Order V — which is probably where I’ll stop — I’ll have to resort to harpsichord recordings, which I’d very much rather not do, but there aren’t many complete sets of the keyboard suites. Only three really great pianists — Glenn Gould, Angela Hewitt, and András Schiff — have recorded all three sets. And when I say what a shame it is that putting the fifth playlist together is so difficult, you can see what has happened to the constraint of the “favorite recording.” Shackles broken!

Composing playlists is hugely laborious, especially if you’re working with a single computer monitor. But you do it just the once (plus fiddling — there will always be fiddling). Then you can listen without choosing.

It probably makes more sense to get a Pandora station going. But then, you may not share my passion for doing my own programming. Then again, if you’re like most of the men I know who listen to serious music…