Museum Note: Pietre Dure

This afternoon, LXIV and I paid a couple of visits to the pietre dure show at the Met. We saw it right after we met up, and then we saw it again after we’d had lunch and taken another look at the Master Photographers show — for which, by the way, there is most regrettably no catalogue.

Which all the more regrettable in light of the fact that the pietre dure show’s catalogue, Art of the Royal Court, is one of the worst that I’ve ever seen. Available in cloth only, it costs $65. I should dearly like to have it as a reference to this exciting show, but I’m not convinced that it would serve that purpose. As a souvenir of the lovely pieces on exhibit, it is wholly inadequate.

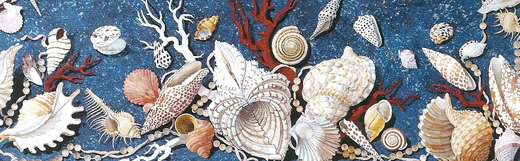

This excerpt from a notecard sold in conjunction with the Royal Court show is alarmingly superior to the catalogue image.

Not that all the pieces are lovely. Many of them are as bad as the portrait of Clement VIII on the Wikipedia page to which I linked above. The real interest of the show lies in dealing with the questions of taste that bristle from almost every object. Essentially the “art” of making mosaics from pieces of hard stone instead of tile, pietre dure work did not come in “affordable” packages, but was for at least five centuries an aspect of exclusive, luxe decoration, capable of manufacture only with the help of substantial state patronage. As such, it bypassed the currents of criticism that informed the more generally accessible arts of painting and sculpture — and architecture as well. Even at its most breathtakingly beautiful, moreover, pietre dure work is unashamedly ostentatious.

Although the odd pietre dure piece is a free-standing work of art — that papal portrait again — most of the important work was designed to enhance furniture of one kind or another, and, aside from a clutch of urns, busts, and other knickknacks, it is two-dimensional.* Tabletops and plaques make up the bulk of the interesting objects on display. It did not take long to discover a rule of thumb: pietre dure work that inclines toward stylization is good; naturalistic representations tend to be tacky.

That’s why I’d like to have the catalogue. Working my way systematically through the exhibit, I would distinguish the pieces that overcome their own virtuosity from the ones that are hobbled by it. There is not one article in the show that was meant to be seen as they are seen at the Museum. The patrons who, long ago, paid for everything would be both horrified and insulted by the simplicity — read, “poverty” — of the exhibition space; the idea of regarding artworks in scrupulous isolation would have struck them as demented. The elaborate, fundamentally jewel-like nature of pietre dure artifacts does not sit comfortably with our persistently minimalist aesthetics. It would be easy to dismiss all of them as garish and, in the over-the-top way that only objects intended for the ruling classes can be, vulgar; more than a few things on display could only be described as “split-level,” with the likes of Tony Soprano the ideal consumer. But there are too many striking beauties in the show to allow a wholesale write-off.

Unfortunately — and the sad-sack catalogue really bears this out — the magnificent stuff has to be seen to be believed.

* LXIV professed a desire to steal most of the urns, and they were lovely; but my memory was wiped clean, as we were leaving the Museum, by the sight of a semi-translucent Fifth-Century marble vase from Byzantium.