Gotham Diary:

Up the Down Staircase

2 October 2013

Wednesday, October 2nd, 2013

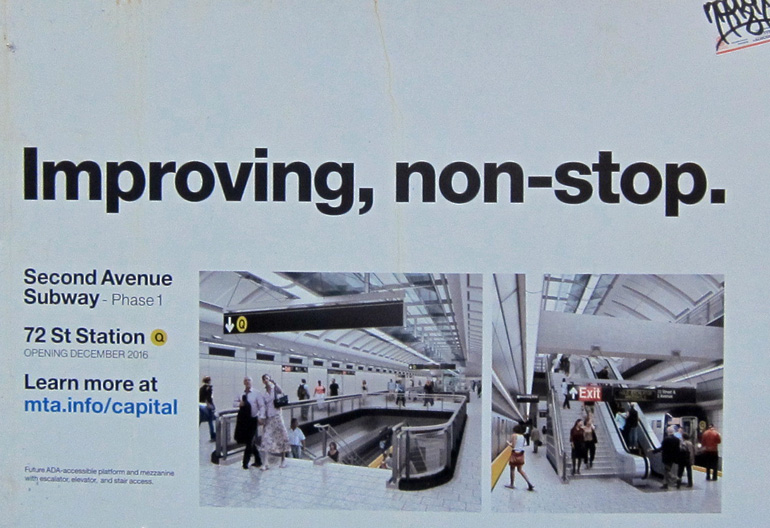

Another sign, posted not far from this one, announces that the work on the 72nd Street Station is scheduled to conclude at the end of this month. There is already evidence of a good deal of dismantlement. Once the superstructures are gone, the sidewalks will be restored, and, years before the subway itself is operational, the streets and the sidewalks will return to normal. Work at 86th Street began about a year later, and is scheduled to end next year at this time. Even here, there are signs of retreat. Of course, there is the fine print aspect: note the “Phase 1.”

It is not uncommon to meet an older resident of the neighborhood who has sworn in blood never to patronise the new subway line, because of the assaultive disruptions that it wrought in everyday life. I am not among them, however. I hope to live to use the damned thing.

You’ll note that it’s the Q train that will be running — originating, thenceforth, at 96th and Second, instead of 57th and Seventh. This route will make use of a previously un- or under-used tunnel that feeds the last major piece of subway construction, the line that extended the Sixth Avenue trains under Roosevelt Island and into Queens. From the Upper East Side, the Q will run along the F (or is it V, now?) tracks through the station at 63rd and Lex (which does not connect to the Lexington Avenue line) and westward beneath the Park, beyond the turn toward Sixth Avenue, heading instead for 57th and Seventh, thereby carrying Yorkvillians such as myself from home to Carnegie Hall in three stops, with no change! Upper Times Square and the Theatre District will be one stop beyond that.

When the “Second Avenue Subway” is extended to its full length, down to the Battery — assuming that such a thing happens — the line will be called the “T.” I don’t plan to live quite that long.

***

The strangest article in The New Yorker: Claudia Roth Pierpont writing about Philip Roth’s literary friends, and how they all laughed. The piece begins with a nice big mention of Veronica Geng, one of the funniest writers to work at the magazine in my lifetime, certainly, and a sadly missed worthsmith. (From a parody wedding announcement: “The bride, an alumna of the Royal Doulton School and Loot University … is also a descendant of Bergdorf Goodman of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Her previous marriage ended in pharmaceuticals.”) Geng was the writer I looked for back in the day. She died of brain cancer in 1997, having long since departed from the post-Fleishman magazine.

Philip Roth, according to Pierpont, was “among her steadiest visitors” at Sloan-Kettering, “sitting on the edge of her bed in order to feed her.” By this point in the piece, Geng has dropped out of the narrative, and is mentioned again only because hers was one of the many graves that Roth would live to stare into. Others would be filled by Bellow, Updike, Plimpton. The article is really about them, the big boys of American writing, 1950-2000. Pierpont’s essay has an indecent feel to it, simply because Roth himself is still alive. Why are we going through his scrapbooks, talking about him, in effect, as if he weren’t there?

I don’t much like any of these writers, myself. William Styron is the only big-shot member of the generation whom I can read with pleasure. Updike was a terrible aphortist, in the way a clever woman can be a terrible flirt. He couldn’t resist! The silken luxury of his mots interrupts the mind and discharges it: further thought is unnecessary. Roth I simply don’t talk about, because I have nothing good to say. He is not, to my ear, so much a bad writer as a mongrel writer, intelligent and common by turns. It is always a mistake to write in a common style, because nothing stales faster. The common writer gets to take his fame with him when he dies — if he hasn’t outlived it.

As for Bellow, I’ve read Herzog twice, but I think it was me, and where I was at, that made the book appealing — I was in the mood for Herzog’s whining. And, when it was new, Mr Sammler’s Planet seemed dire, set in a New York City denuded of glamour. I recall The Dean’s December with fondness, perhaps the Rumanian scenes were drolly exotic. But I had to put down The Adventures of Augie March midway, when it seemed that everyone was about to go to Mexico. Pierpont writes that Roth, almost paralyzed by admiration for Bellow’s first masterpiece, was “in thrall to its capaciousness, its ebullience, its startling reinvention of the American idiom.” My calendar of errors exactly. “Capaciousness” — how about exurban sprawl? A nightmarishly episodic disinclination to learn from the past? “Ebullience” — I don’t want to try to follow a novel that behaves like a puppy. As for the American idiom, it were far better to forget it than to fiddle with it.

That last crack is something of a pot-shot, because I do believe that Bellow’s manner of bathing American lingo in Jewish intentionality was transformative, and arguably the one positive change that American English has made from British English. It is not a matter of Yiddish expressions, although the ghosts of speech-patterns are palpable. Rather, Bellow assumes the plain, not-fancy seriousness of the Talmudic scholar, and proceeds to wrestle the jokey thoughtlessness of American speech to the ground.

But Augie himself was too much for me. There was too much of him. Had Bellow’s novel run the length of Candide, I’d have been impressed. But, adventure after adventure, Augie kept coming back for something new and different. Far from leading a life without a second act, he was, when I left him, about to embark on a seventh or an eighth.

***

There’s great food for thought in Thomas Friendman’s Op-Ed piece today: “Our Democracy Is at Stake.” Because Friedman’s call for majority rule in the United State, which he finds to be thwarted by the Tea Party opposition to Obama and Obamacare, parallels that of the Muslim Brotherhood for majority rule in Egypt. (This is not a point that he makes.)

The voters who put the Morsi regime into office wanted (presumably) to live in an Islamist state. The voters who put Obama into the White House, and most representatives on either side of the aisle into Congress, want to live in a pluralist state. Each faced and continues to face a determined minority opposition. In Egypt, the army came to the aid of that minority. Such an outcome is unlikely in the United States, but this doesn’t mean that our minority will not do everything it can to express (and not just talk about) its opposition. Sadly, neither nation offered or offers a procedure for exceptions within democracy.

How do the Swiss organize the respective cantons’ official languages? That might be worth looking into. There are a lot of Americans who want to live in what, for simplicity’s sake, we’ll call a “white” country. I don’t think that skin color is actually that important; it’s simply shorthand for a constellation of attitudes. Somebody like me, for example — a Northeastern intellectual feminist who would no sooner use a firearm than mount a Jetski — would be far more unwelcome in “White America” than a respectable, churchgoing dry-cleaner who happened to be “of color.” I know; I lived for several years in Texas, and spent as little time outside of cosmopolitan Houston as possible.

Would I say that my sojourn in the Lone Star State taught me to respect other people’s values? Yes and no. I don’t respect the values themselves, but I respect the fact that people are going to hold onto them until a deep personal experience inspires them to make a change. And I know that that deep personal experience is not going to be initiated by blather from the likes of me. How do we agree to share common ground? Might we not begin by acknowledging that we don’t share common ground in the first place?

Why does Obamacare have to be the law of the land? Why can’t it be a program of federal assistance that states or localities must opt into? It’s true that I would make this request anyway, even without the “shutdown,” because I believe that medical care is so vastly confused that no attempt at overriding improvement can fail to make things worse in a lot of cases.

In another Times piece — this one inherently interesting — Eduardo Porter suggests a very sensible explanation for the opposition of Republican extremists to Obamacare, as well as for John Boehner’s complicity in their coup:

Even Americans who say they dislike the law actually like many of its components. Nearly three-quarters approve of giving financial help to poor and moderate-income Americans to buy health insurance. Two-thirds approve of barring insurance companies from denying coverage because of somebody’s medical history. Three-quarters favor letting children stay on their parents’ insurance until they are 26.

Until now, social welfare programs in the United States have exhibited a “big hole,†Professor Skocpol said, consisting of nonpoor working-age Americans and their children. Obamacare closes a big chunk of it.

“The main beneficiaries tend to have lower wages, employed in smaller businesses that are not providing health insurance,†she said. “They are not elderly. They are also not the poorest.â€

And they might be grateful to Democrats for the benefit.

To conservative Republicans, losing a large slice of the middle class to the ranks of the Democratic Party could justify extreme measures.

Perpend.