Even though I’ve got a bit of sore throat, and could really use a day at home (writing writing writing), I got myself to the Morgan shortly before eleven this morning for an outing with Quatorze and Lady D. (Lady D, although new to these pages, has been resident in New York City for nearly fifty years, a stylish British secretary right up to her retirement from an eminent foundation — and still stylish.) It was all my idea: we would look at the two world-class illuminated manuscripts that (a) happen to be domiciled in our fair city and (b) have been unstitched for one reason or another, making it possible to mount all the interesting pages at once.

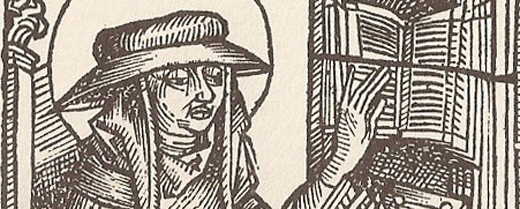

Of course, no one but specialists knew about the more recent of these manuscripts, the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, until the day before yesterday. The prayerbook, broken up into two books by an unscrupulous dealer in the 1850s, had only recently fallen completely into the Morgan’s possession. The sheer novelty of the book’s presence in New York harmonizes deliciously with the novelty of the book itself, which is not your father’s book of hours. Indeed, it seems designed to suit a post-modern agenda. Scurrilously humorous marginalia are a hallmark of medieval devotional manuscripts, but the trompe l’oeil jewelry (a rosary, a necklace, some gold coins) and the outsize naturalism (moths, shellfish, pretzels) completely up-end any idea that you might have of Fifteenth-Century miniatures, while the scenes in the margins often upstage the vignettes at the center of the page. The jokey quality of this book of hours is best characterized by the utterly immodest image of the donor/owner herself in the margin of a vignette featuring Mary and the infant Jesus. Mother and Child appear in timeless attire, but Catherine has the air of an ambitious hostess from Massapequa who has just tottered off the LIRR with only seconds to spare for her lipstick. It is not surprising to learn that Catherine spent the better part of her marriage waging war on her husband. Military war, that is, with battles and dead soldiers.

In other words, the Hours of Catherine of Cleves really does belong here in New York.

The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, also belongs in New York, because it is best known for not being the Très Riches Heures of Jean d’&c, which belongs to the collection at Chantilly, outside Paris. Fantastic as the TRH is, I’m devoted to the Belles Heures, and have been ever since I first saw them, many long years ago (more than forty), at the Cloisters. I can say, I think, that this creation of the Limbourg brothers (natives of Nijmegen, it seems) is the first work of art that I loved on my own and just for itself. Of course, it is not just a work of art. It has a literary/liturgical quality that, as regular readers of this site will not have to be told, made a profound impression on my teen-aged mind; the “book of hours” is more than ever a construct with which I live in deep communion from day to day. I may not be a believer in the higher object of the book of hour’s devotions, but its varied regularity is sacred to me. And it is so taken for granted that I can see how beautiful the art of it all is.

The borders of the vignettes (illuminations) of the Belles Heures are relentlessly uniform, with only the smallest variations placed among the sprays of ivy that delicately frame quire after quire. The vignettes themselves, however, are magnificent final expressions of medieval narration, where space is temporal as well as physical. (See the illumination of Gethsemane, for example.) In contrast to the vignettes in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, which are earnest but rudimentary early-Renaissance scenes, the illumination of the Belles Heures is accented by Gothic arabesque. There are crowd scenes that might remind you of Giotto, until you remember that Giotto called a halt to that sort of medieval shimmying and swaying. The compositions of the Belles Heures are Giotto, if at all, before Giotto.

The parade of spot-on images exhausts any idea of comprehensiveness. The Office of the Blessed Virgin begins with the Visitation of St Elizabeth and ends with the Flight into Egypt. The Office of the Passion begins with the Agony in the Garden and ends with the soldiers asleep over an empty sarcophagus. Catherine of Alexandria is the subject of a virtual novella, and the stories of St Jerome, of Saints Paul and Anthony (with their red Red Sea), and of St Bruno and the Chartreuse all inspire mini-cycles of illumination. The suffrages — miscellaneous prayers to the saints — bring stirring dramatizations of the doings of Saints George, Nicholas, Ursula and Charlemagne (!), and of course St Michael the Archangel. Amidst all this colorful glitter, the somber grisaille of Passion’s Nones is almost lowering.

In between our museum visits, we had a jolly lunch at Demarchelier. Lady D told us about the appalling organist at her parish church, which is down in Turtle Bay. The woman is not so bad at the keyboard, but she can’t carry a tune to save her life. There came a moment when Lady D could stand now more, and she stopped her ears with her fingers. This was, unsurprisingly. noticed. After the service, the harpy asked Lady D if “she had a problemâ€! Indeed she did, our Lady D, and “since, after all, she did ask me, I told her what was wrong.†Whereupon the organist demanded Lady D’s name (she didn’t get it). Imagine such goings-on! At dinner, Lady D’s story was repletely corroborated by Kathleen, who, for reasons of her own, has sat through many services at the selfsame church. One thing’s for sure: neither Catherine of Cleves nor Jean de France would have put up with such incompetence. But that’s what the Church has come to, no?Â

Â