Gotham Diary:

Opera and Its Discontents

Thursday, 23 June 2011

Thursday, June 23rd, 2011

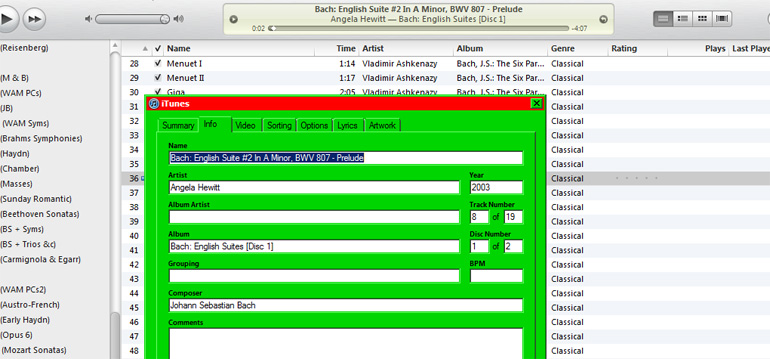

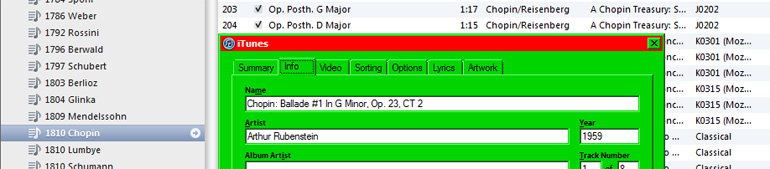

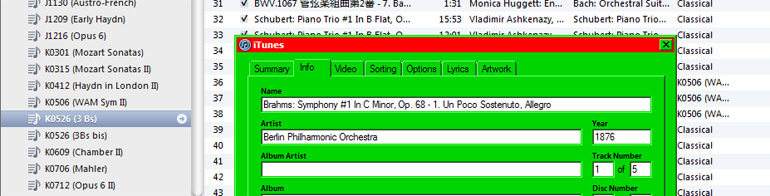

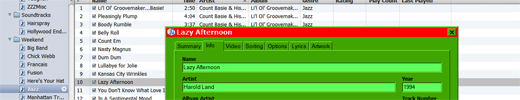

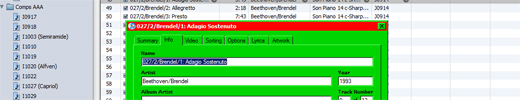

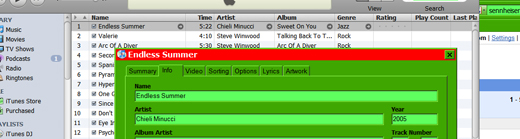

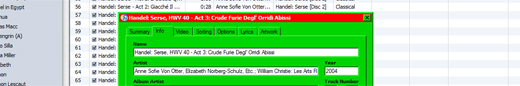

The other day, I bought an iPod. Now he’s lost it, you’re thinking; how many times has he bored us silly with his Nano Notes? But this time, it isn’t a Nano, but a Classic iPod, or iPod Classic. It looks like a Nano that ate one of those cookies in Alice in Wonderland. It is quite ridiculously large. But with the storage to match (about ten times the capacity of a Nano), it is the perfect place for my opera collection, or as much of it as will fit. Every day, I load another five operas onto the thing. I still can’t listen to opera if the page that I’m writing requires actual thought, but as you can see there’s nothing here that Un Ballo in Maschera (Bergonzi, Nilsson, Molinari-Pradelli) would get in the way of.Â

It’s Thursday, which means that I’m planning to go downtown in a few hours to sit with Will while his parents have dinner alone somewhere. Tonight, I am going to take a bunch of the shirt cardboards that I’ve been hoarding. There was a time when shirt cardboards were the joy of my youth, and I got in a lot of trouble once for advancing myself the cardboards from my father’s shirts drawer. For a while, I was very into constructing hybrid castle/stage sets. I was very into hidden doors and secret passageways, and even though these were not easily realized in shirt cardboard (which at least had the merit of being stone grey), it was exciting to create three dimensional models of the houses of horror that I hoped to live in some day. I have no memory of outgrowing this pastime, so maybe I didn’t. Maybe it’s going to blossom again in the guise of “playing with Will.”Â

Being with Will is always quite straightforward — we do this, we do that — but remembering my time with him is quite strange; it’s as though I were reviewing my recollections through someone else’s prescription glasses. It is impossible, when he is not actually in the room, to think of him as a child of nearly eighteen months. There are too many precocities, or at any rate moments when I feel that I’m with a teenager, or a third-grader. There are shards of his personality, as it were, that are already fully grown. They’re surrounded by undeveloped parts, sort of like a Roman Forum but under construction, not in ruins. Most of what he says is still — unintelligible, and it’s not always clear that he knows what talking is for. (Or, rather, what it isn’t.) But he appears to understand a great deal of grown-up talk. Like his mother, he has a formidable memory, and just because he hasn’t been exposed to something in a while doesn’t mean that the unguarded mention of it won’t kindle an insistent interest. (When in doubt, I spell things out.)Â

He’s also “musical” — he dances, bangs drums, and even riffs on the harmonica. There is a spectrum of his vocalizing that could be called singing, sort of. But we are a long way from Aida. There has been no listening to music at our house. When he and his parents come to dinner, there might be a jazz playlist purring away somewhere, but not loud enough to catch Will’s notice. And when he’s here with Kathleen and me, we somehow don’t think to play anything — except, of course, for Shaun the Sheep. There’s step dancing in Shaun, which Will gamely attempts to imitate. It is mostly a matter of shaking his butt. If there’s one thing I’m looking forward to, it’s taking him to see Paul Taylor. There are always lots of kiddies in that audience. But although it’s very easy to imagine Will sitting rapt through a twenty-minute dance, it’s also easy to imagine that he might respond in a manner more typical of his age. Pretty soon, I expect, I’ll be learning all the minimum ages. At the Museum, happily, there isn’t one, but you have to be ten to get into the Frick. If he keeps growing at his current rate, Will will pass for ten when he’s eight.

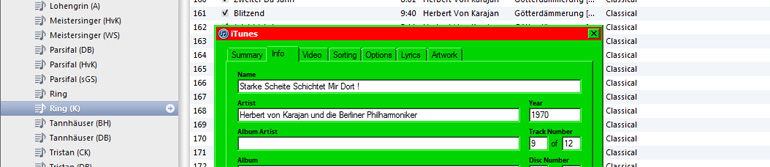

But I mustn’t push things. I must remember what happened when a friend of ours was taken, as her first opera ever, to Parsifal. Amazingly, her date’s passion for this masterpiece proved not to be contagious in the least!