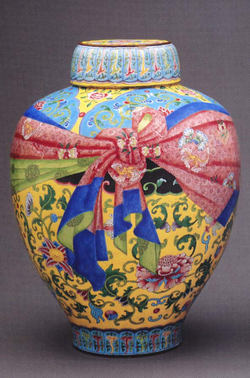

Photo by Kathleen Moriarty

Until last Thursday, Kathleen and I were planning to go to Venice in September, to celebrate our thirtieth wedding anniversary. Some time ago, concluding from the debris of our junked plans to visit Italy for the first time, that we’d never get there until we narrowed our ambitions to a few days spent in one city or the other, I’d asked Kathleen to choose between Venice and Rome, and she chose Venice. But on Thursday, she changed her mind in favor of another island, this one much closer to home. At dinner, Megan had said that she would like Will to spend some time on Fire Island this summer. What a nice idea, I thought — but I mentioned that Kathleen was already busy planning Venice (as well as a business trip to Amsterdam in May).

Little did I know. When Kathleen got home from a bar association meeting, I told her Megan’s wish, and she got right online and scouted the offerings for a few hours. Before we went to bed, she had four very attractive rentals in mind. The next morning, Kathleen decided that what she wanted in the way of an anniversary present was not a few days in Venice but a month of weekends (at least) with Will and his parents, on a beach where she’d been very happy as a child. The glamorous pleasure of top-drawer sightseeing in a distant Oz was replaced by the richer one of extended family time on a local sand bar. If I’m a bit wistful about Venice, it’s probably because I don’t have to travel there, not for the moment, anyway. And a month on Fire Island is actually more fun to look forward to.Â

We change our plans fairly regularly in this household, which is why I avoid mentioning them. I was looking forward all week to Paul Taylor on Saturday. I’d had the bright idea of making a day of it, and seeing both a matinee and an evening show. It did not threaten to be an ordeal; in the three hours between the events, we’d do some shopping and have an early dinner. And that’s exactly what happened; it couldn’t have been simpler. When the matinee was over, we cut through the arcade that runs for four blocks south of 55th Street to 52nd Street, where there’s a men’s clothing shop that I like and that is never open when I’m in that part of town; and then we went to Cognac, where we enjoyed a very leisurely meal. Instead of shooting back to City Center, we walked up a bit to Carnegie Hall, so that I could take some photographs that I might use as decoration here. The second show let out at about ten, and we dashed for a taxi. We were home by 10:20, exhilarated but nicely exhausted as well, our brains still popping from the day’s workout.Â

No doubt because I happen to be reading James’s Gleick’s The Information, I’m seeing and recalling Paul Taylor’s dances as fountains of information — fountains as fancily up-to-date as Mark Fuller’s celebrated installation at Lincoln Center. No: fancier. Most information that we process as such comes to us in streams that are comprehensible because they’re filtered according to overall expectations. Within the context of dancers moving voicelessly, Taylor tells us a lot of things that we don’t expect to hear, not in the order in which we hear them. A good deal of it looks meaninglessly decorative, but if we suspect that this appearance is misleading, that’s because the vocabulary of movement, no matter how wide-ranging, is coherent. What seems decorative or unintelligible is as much a part of the story being told as the bits that we easily get (fists shaken at heaven, for example, in The Word, or in the very different Phantasmagoria). Taylor tells his stories in his own kind of time; it is not the linear sequence of narrative but something more neural. Meaning often feels short-circuited, as if too much information were being pushed through too narrow a pipeline; and yet this effect always seems quite calmly planned. A lot of information is addressed to parts of my brain that know nothing of logic or history. I don’t know if I’ll ever put much of it to use, but I enjoy taking it in.Â

We very much liked four of the six dances that we saw, including one of the premieres, Three Dubious Memories. This dance, which Alistair Macaulay didn’t much like, overtly foregrounds three little love stories, involving a man in green, a man in blue, and a woman in red (Robert Kleinendorst, Sean Mahoney, and Amy Young); and in each iteration the point of view is that of the exluded lover. Behind them, however, a chorus, dressed in grey (and led by James Samson), plays out a larger drama that is not so easily grasped. Indeed, this dance subverts the very idea of a chorus. Here, the chorus does not comment responsively on the colorful romances but rather it resists them, as if to remind us that life is more complex than boy-meets-girl. The choristers warn, they agonize, they resign themselves. They even try out the lovers’ gestures, but experimentally, not reflectively. The lovers, for their part, ignore the chorus, and their movement is designed to look spontaneous. The effect is oddly like that of a Bach chorale, with a steady, singable tune cutting through highly worked, almost complicated counterpoint.Â

I must say a word about Company B, which is set to pop songs sung mostly by the Andrews Sisters but in two instances by Patti Andrews alone. Santo Loquasto’s costumes, always interesting, are here truly superb: clothed in generously-cut, pale-colored outfits laced with bright red belts, the dancers are animated by a period ease recognizable from the old movies; but unlike the studios, Paul Taylor does not want you to forget that this is a ballet set in war time. At the end of his number, the Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B (Robert Kleinendorst) falls dead under fire. It is a moment, as they used to say, of great pathos.

The Paul Taylor Dance Company is made up of sixteen dancers, some of them starrier than others. Everybody gets a chance to shine, but some manage, by whatever theatrical alchemy, to make more of the opportunity. The tension between dancers’ distinct personalities and their mastery of the common Taylor idiom is one of the company’s wellsprings of excitement. The wonderful Annmaria Mazzini danced her last season with the company this go-round, but she leaves behind three full-blooded peers in Amy Young, Parisa Khobdeh, and Laura Halzack. It’s harder to foresee what the inevitable loss of Michael Trusnovec, the company’s senior dancer, will do to the make-up. The only dancer to remind me of him is the most junior, Michael Novak; both are sly understaters who pull of the stunt of making a complete spectacle of art concealing art.

Robert Kleinendorst, on the contrary, is a virtuoso on the lines of Robert Downey, Jr or Johnny Depp; morsels of the scenery are always disappearing into his brilliant smile. In her nice reflection on Paul Taylor and this season’s performances, Gia Kourlas calls James Sansom “rigorous,” and this seems just right, if not the whole story; in Company B, donning a pair of horn-rim spectacles, Mr Sansom teases the girls in “Oh Johnny Oh!” so bewitchingly that Laura Halzack walks away spouting a spoken line: “Oh, phooey!” Of Ms Halzack, Kourlas writes, “Laura Halzack is the most versatile and beautiful company member: versatile because she’s not afraid to appear uncomely, and beautiful because she has a sense of humor,” and that seems just, too, except that, er, Laura Halzack is beautiful.

Sunday was a wet and gloomy day, and sensible people everywhere stayed at home. But Kathleen and I ventured forth to take Will for his Sunday walk, which may or may not delight him but which gives his parents an hour or so of precious time to themselves. At Tomkins Square Park, the very air was sodden, and there could be no thought of sitting on a bench of putting Will in the swings. What Will did want to do was to splash his hands in the small puddles that accumulated on the railing surrounding the dog run. He was very entertained when Kathleen flicked at the water herself, sending it flying. (This turned out to be a trick that I could not pull off.) We pushed on toward Third Avenue and the St Mark Bookshop, our usual turning point. Back in the literature shelves, an attractive Japanese woman asked with great decorousness if she could take a picture of the “cute” little boy. When she had done so, she petted Will lightly on the shoulder and murmured “arigato.” Kathleen decided that the woman must have been as surprised by a child’s being carried by a man as she was delighted by Will’s appearance, but I wonder if this is entirely fair. Â