Scroll down for Boxing Week updates. (26, 27, 29, 30 December 2011; 1 January 2012)

This is the time of year when all the great stories are family stories, and therefore private, not for sharing even at Facebook. But it’s grand to know that the Internet is there when you’ve maxed out on personal input. Here’s the Internet equivalent of stepping outside after a close family gathering and having a smoke: What would Voltaire have made of the Internet? What would the Internet have made of Voltaire? The second question is easy. Basic biographical material about Voltaire includes the gaming of a lottery that made the man a millionaire. It was legal, but just. It would be pretty to think that Voltaire became a self-supporting philosophe on the proceeds from Candide. Pretty.

Meanwhile, you should see the hat that Kathleen is knitting for me! Production is in its final phases as I speak. It is so capacious that I can pull it down over my mouth — but of course it will shrink in the first wash. We were arguing about how to finish it, with a tassel or a pompom. About pompoms, Kathleen said, “I know how to make them; I’ve just never done it.” I might have gone along with this assurance if I hadn’t just read Daniel Kahneman. We’re settling on a jingle bell. There’s always next year.

Ray Soleil says that Will will never refer to me as “Doodad” to his peers, and that’s probably correct. What I’m wondering, though, is whether Will will agree with the tens (I could have said dozens) of children who have pointed me out to their mothers and said, “Santa Claus!” Will Will be the opposite of Virginia O’Hanlon (thanks, Eric!), writing to the papers to insist that Santa Claus is not only real, but a denizen of Yorkville to boot?

Almost certainly not. Will will understand from the get-go that Santa Claus can’t strew gifts beneath a tree if he doesn’t have chimney access. Even if he is your Doodad, and, boy, have I got presents to strew!

The other story about Voltaire that I’m fond of tells of his colossal, almost suicidal indiscretion at Fontainebleau, which he visited with his mistress, Mme du Châtelet, during the palmy days of Pompadour. Bored after a spell of standing in the room where the courtiers were playing cards, he leaned over to his lady-love and stage-whispered, “How can you play with these cheats?” First, they were lucky to escape the château alive before midnight. Second, see the part above about gaming a lottery. My father used to say that I had more books than sense, but I’ve often thought that Voltaire had, although even more books, less sense. That’s why I keep him around. Also, he kind of looks like Dad, my dad.

Boxing Day

I’ve little more on my mind at the moment than registering that I’m alive, and tolerably well, after a couple of lovely, lucky days of Christmas. I had planned things prudently, and luck threw me a few good turns. When we sat down to dinner on Christmas eve, it wasn’t with the same people we’d expected to dine with, but, all in all, an improvement: my adorable grandsom, whom we used to call “Mr Dinner Party” because would sit through an entire dinner and eat almost everything, has developed a healthy little boy’s aversion to the idea that eating involves sitting still, or, for that matter, mealtimes. The perfectly-roasted rack of lamb would have been quite thrown on away on him, and on his parents as well, as his mother assured me. But thanks to unforeseen changes in the holiday plans of two of our oldest friends, we did not dine alone.

Exhausted by the foregoing paragraph, I have to go back to bed.

Tuesday, 27 December

The bed has been made, and the kitchen straightened out; the handyman has cleared out the bathtub that clogs up once a quarter at least. Kathleen is about to take the last of the calendars to a mailbox; they’re all stamped and ready to drop. In a few minutes, I’ll call the dry cleaner to summon our semi-weekly trade of dirty laundry for clean. It could not be more ordinary, what’s in store for today — which I hesitate to say, given the fact that the Fates are avid readers of this site and take a keen pleasure in “posting comments.” (By the way, comments are open, once again, at The Daily Blague. More about that some other time.)

Now, here’s how ordinary today is: I turn on the CD player and it picks up at the start of Mozart’s Horn Quintet, almost certainly his most disappointing chamber work. It’s not a chamber work, really, but just a stripped down horn concerto, so brainlessly breezy that it always sounds to me as if it’s about to veer into Ein Musikalischer Spass — that parody of the bubblegum music of Mozart’s time. Mozart was probably as incapable of writing such stuff as good writers are of turning out lucrative pornography (does anyone still read pornography?), but his musical joke captures the essence of hackery-quackery, and it makes us laugh at it.

At breakfast this morning, I read the excerpt of Pico Iyer’s memoir that appears in the November issue of Herper’s, “From Eden to Eton.” People seem to think that I know everything, but I did not know who Pico Iyer was until this morning. That’s to say, I didn’t know what his family background was. It seemed too improbable that a subcontinental father, no matter how learned would name his son after the great (and unread) Renaissance humanist, but that’s what happened. Also, there’s a reason why Iyer seems to have come from everywhere; at the age of nine or ten, he went back to the Dragon School at Oxford, after a year or so in Santa Barbara. I see that he was also the head of the Chess Club at Eton. Now, this is what I have in mind when I insist that I am an ill-educated lout.

Thursday, 29 December

The good thing about the colds that we catch from Will throughout the winter is that they don’t last as long as the the other kinds of colds — colds that we are glad to catch only rarely. Will’s colds come and go in three days. But the first day is usually pretty incapacitating. Being an ancient creature, I’ve learned that the surest way to recovery is to drop everything, stay home, watch videos, and order Chinese. And no email underf any circumstances! That’s what works for me. Kathleen went to work yesterday, and so she’s having a rather more incapacitating day today than I did yesterday. In a little while, I’m going out for a haircut.

I watched five movies. The first one was Get Low, which I’d bought on sale at the Video Room but never watched. This is the movie about the reclusive carpenter who wants to throw himself a funeral party that he can attend. Robert Duvall plays the old man, but the movie’s quirky tone is set entirely by Bill Murray, that master of plangent, unfunny comedy. I almost watched Winter’s Bone afterward, but instead I watched something with an actress who to my eye closely resembles Jennifer Lawrence.

All four movies, after Get Low, were in fact drawn from the same drawer of DVDs, which runs from M to P. First, I watched Nurse Betty, which I hadn’t seen in a long time. Then I watched an action movie in which Aaron Eckhart is as slick as he is sloppy in Nurse Betty: Paycheck, with Ben Affleck and Uma Thurman. This was followed by The Queen, also an action movie but utterly devoid of the mano a mano that clutters up Paycheck. Finally, a real drama: Quiz Show. Appalling to note: Quiz Show is nearly eighteen years old.

I suppose I ought to say a word about each of these movies. Renée Zellweger is astonishingly lovely in Nurse Betty, with her beautiful complexion and bewildered ingenuousness filling the screen like a perfectly-ripe peach. It’s fun to note the difference between her natural self and the persona that she puts on while in the fugue state occasioned by witnessing her husband’s murder. As “Nurse” Betty, she utters soap-opera banalities (“You said it to her, but you meant it for me”) with Shekespearian authority. Morgan Freeman’s character is, in contrast, a sentimental mess, something that the actor is almost capable of making us overlook. The day’s other movie about television, Quiz Show, is a requiem for dreams of the golden age of television, which never happened. Television was always bound to be crap, partly because of the advertising model, which poisons everything it touches, and partly because television flatters our overconfidence, making us feel that we understand things that we don’t understand at all. But lots of people had high hopes for it in the Fifties — “the largest classroom in the world.” (Education has stumbled so badly that this may indeed be true today.) Quiz Show reminds us that television never had much of a place for the Herb Stempels of the world.

You may be surprised to read that I like Paycheck — every once in a while. I don’t care for all the fighting or car-chasing, and the “clever” plot does not bear much scrutiny. But Paycheck works as a video game that you don’t have to bother to play yourself; you can just watch and enjoy it. And things that are really wrong with the production — namely, Uma Thurman — keep things frosty.

There’s nothing to be said about The Queen that hasn’t been said already a million times: Helen Mirren is breathtaking, &c &c. By the time this last video was ending, Kathleen came home. What she always finds puzzling (and so do I) is Diana Spencer’s enormous popularity with ordinary people. We can only attribute it to sensibilities coarsened by — television.

Friday, 30 December

Perhaps it was premature to blame our illnesses on Will. They’ve settled in — a cold for me; and sore throat with attendant aches for Kathleen — and threaten to stay a while. We’re taking it easy, but there’s only so easy you can take it at this time of year, when, for example, friends have been invited to drop in on New Year’s Eve afternoon (that would be tomorrow). We could call everyone up and cancel, but we’re not that sick, and a few friends might find the Let Things Go look an interesting change.

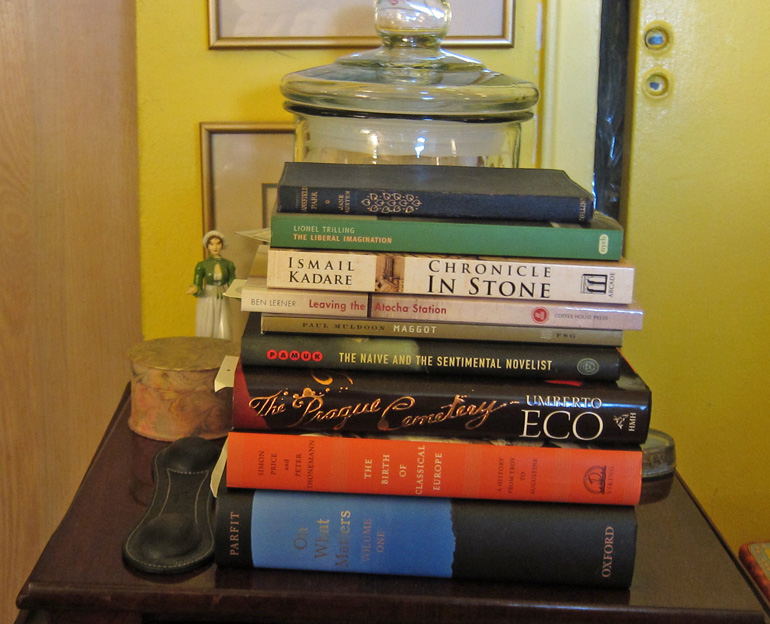

I’ve spent the entire day reading. I’ve been reading a great deal, actually, which is very nice. Reading books, I mean. By books, I don’t mean printed books as opposed to ebooks; I mean books as opposed to magazine articles and Internet feeds. I’ve been marching through Jeremy Black’s George III, enjoying the odd bit of donnish humour, as in this remark about bad behavior among the Hanoverians, made of George’s father, Frederick.

As Frederick, however, did not become king, he left to his grandsons, George III’s numerous progeny, the task of recreating the monarchical habits associated with Charles II.

(What makes this funny is the satire of duty: tasks and monarchical habits were assiduously avoided by these gentlemen, crowned or not.) As I read along, I become more and more convinced that George is the present queen’s truest forebear; like him, she is shy but unshirking, modest but determined, and she knows her onions.

I have also read three smallish books that have been lying about for quite some time. I wasn’t in the mood to read any of them until this strangely blended season of holiday cheer and mourning, stretched out over a barrage of minor ailments and now this cold. (As to the mourning, the shock of my aunt’s unexpected death has not yet found its depth.) The first book, Michael Kimball’s extraordinary Us, I envisioned as an experimental downer, and regretted having been sold by its enthusiastic reception in the more interesting precincts of the literary Internet. That was before I read it, though. Once I began, I couldn’t stop. It took my a while to notice the typographical signals that differentiate Kimball’s recreation of the final chapter of his maternal grandparents’ lives from Kimball’s personal recollections, but the former is so fresh and simple and vigorously written that I was slow to realize that I was reading about elderly people. “Our bed was shaking and it woke me up afraid,” the book begins. What follows is a cordial distillate of the stream of consciousness into which medical emergency casts the victim’s nearest and dearest. Here is the husband in the hospital parking lot, distinguishing people in his situation from the hospital staff:

We looked anxious and walked fast. We were all hurrying into the hospital to see if there had been any change in our husband or wife or mother or father or son or daughter. We wanted to know if anything had happened to them while we were at home or asleep. We wanted to get up to their hospital room before they woke up or before they died.

It’s the kind of writing that makes Hemingway look baroque. I don’t think that I’ve ever seen the generality of mortality so clearly fractured by the prism of an individual’s particular experience.

Then I read Chester Brown’s Paying For It, the graphic memoir about getting satisfaction from prostitutes (and tipping nicely for the experience). So far as the story goes, I wound up wondering if the nearer degrees of the Asperger’s spectrum might very well range through a sizable chunk of the male population. But that’s not the point of Paying For It — the story, I mean. The point is the graphics, and the graphics, while austere, are illuminating. What they principally illuminate is the distortion of memory. You can tell what the narrator remembers by the number of frames that he allocates to each experience. The suspense of wondering what a prostitute will look like when she finally opens the door appears to be far more memorable than the boffo sex that did (or didn’t) follow. This makes sense: only adolescents believe that great sex is unforgettable. Or, rather, that it is ever anything more than “unforgettable” — once it’s over, that is. Although my carnal circuity (to use Nicholson Baker’s great phrase) is so different from Chester Brown’s that one of us might just as well have been a Martian, I found Paying For It to be an extremely interesting narrative of consciousness.

The third book was Chris Bachelder’s Abbott Awaits. I read Aaron Thier’s strongly favorable review in The Nation, and ordered the book from my local shop. Right there you see the problem, or at any rate I do: Abbott Awaits is one of the great novels of 2011, possibly of modern times, but I read about it in The Nation and had to order it. This is the kind of funny/poignant book that you’d think everyone would be cdrazy about. Maybe it’s a bit too spot-on.

To tell the truth, I’m not sure how much of a novel it is, seeing how congruent the eponymous character’s life is with the author’s. It makes more sense to see Abbott Awaits as a reconsideration of The Myth of Sisyphus. A very funny reconsideration, I hasten to add. In about 9o brief chapters, Bachelder captures the existential quandary of an average sensual humanist. We have seen this character many times before; he is usually the hero of any novel written by a “trade” novelist who happens to be a man, and the butt of countless jokes when the upscale novelist is a woman (Alison Lurie, say). Here is the gamut of his character, from this —

Abbott has never told his wife this — he’s never told anyone — but he has a vision of himself as a father who, in the most gentle and loving and supportive way, corrects his children’s grammar. At the dinner table, say, buttering a roll and explaining, affably, the uses of lie and lay, for instance, or which and that. His intention is certainly not to demean or humiliate, and neither is it simply to instruct, really, but to share his passion and respect for the amazing system of English, its intricate rules and odd expressions.

— to this —

Abbott’s wife, inside the house, comes to the kitchen window below the section of the gutter that Abbott is cleaning. Her face in the window is level with his thighs, so naturally he imagines her sucking his penis and swallowing his semen.

It’s that “naturally” that clinches the portrait. The thing about these guys is that they are never sufficiently engaged by any job (other than polishing their egos) to let the slightest possibility of getting their rocks off go unsniffed. But that is not the particular Sisyphean fate that interests Bachelder. Fatherhood is, in its modern parenting phase. I’m not sure that Abbott Awaits is the book that progressive and intelligent new parents ought to be reading, but it is certainly all about them. And that’s how Bachelder comes up with an answer to life’s questions that’s somewhat brighter than Camus’s. For most exhausted and demoralized parents, it is despair that drowns in the bathtub, not the baby.

1 January 2012

The beginning of the new year would seem to be the ideal raison d’être for a fresh blog entry, but Kathleen and I remain mired in our respective ailments. This morning, I awoke so tired that I feared I must have reached the final hours of my life. But after an hour in my chair, spent discharging the night’s effluvia, I felt well enough to go back to bed and sleep some more. By noon, I felt more like someone with a bad cold than an impending corpse. Kathleen’s fever still dances around 100º, and of course we’ll have to call the doctor first thing Tuesday if this goes on.

We watched Radio Days last night, but that was our only New Year’s Eve observance (an annual tradition since shortly after the film came out, in 1986). There was no caviar, no champagne, no standing on the balcony listening to the revels and the fireworks. We had a happy time of it nonetheless. I’m delighted to have made it into 2012. 2011 wasn’t so much a bad or a hard year as a seemingly endless continuation of the “year” that began in October 2009, when I rolled up my sleeves and resolved to master my household. Since that may not sound like much of a challenge, I’ll tell you the story.

Way back in the Eighties, when I ought to have been arranging our domestic affairs (an undertaking that involves uncluttered closets, realistic budgets, and all the 0ther things that self-help books talk about, but also a lot more, stuff that you have to figure out for yourself, because your household is as intimate as your personal hygiene), Kathleen and I bought a country house instead. This gave us unlimited room for growth, as it were. When, about ten years later, the folly of running two households became impossible to ignore, we sold the house and filled a large storage unit with its contents — all but the furniture, which we simply got rid of.

This was my second chance to master my material posssessions, but instead I found another, if worthier distraction: the Internet. I launched a Web site. Then, a few years later, the antecedent of this very blog. I gave householding no more attention than absolutely necessary.

If there was a breakdown or crisis in 2009, I don’t remember it, but I remember waking up to the awareness that I couldn’t live like this anymore. Why, for example, did I maintain such an extensive batterie de cuisine if I hardly ever cooked? When was that loveseat, last reupholstered by my father in a material that neither Kathleen nor I could bear to look at, hidden by an increasingly tattered slipcover, going to be made truly presentable? What was the point of storing so many framed pictures? These are only three of a hundred such questions, all of them insistent and annoying.

When you are young, you believe that you can simply throw everything away and start over. This is like believing that you can lose twenty pounds and keep in shape. A lucky few get to pull it off, but for most of us the more realistic course is to avoid accumulating the excess. If you are the sort of person who is inclined to believe that almost anything will come in handy — a romantic delusion encouraged by reading, at too tender an age, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe — this will be difficult. You may easily find it easier to maintain your youthful waistline than to keep your closets in good shape. (And by “good shape,” I mean the state in which, when you’re in need of something, you know right where it is, and all you have to do is open the closet door and reach for it.) The worst thing about being young is that you have no sense of how likely something is to come in handy — handy to you. You don’t know who you are when you are young. You only know who you want to be. That said, I wish that I’d buckled down to the job in my mid-thirties.

There is another cruel fact of life that is even more difficult to learn: Nobody wants your stuff. Aside from the odd objet de vertu that prompts people very rudely to ask you to leave it to them in your will, nothing that you own is of any real value to anyone else, especially if you life in a relatively affluent society of fungible goods. Lets say that there’s a “market” for my collections of books, CDs, and videos — and it’s by no means certain that there is — there remains no end of other kinds of items that you’ve probably piled up in such large heaps that it’s not worth anybody’s time to search for valuable nuggets. I’m talking about mementoes — scrapbooks and yearbooks and photo albums and shoeboxes full of photographs, recipe cards, letters, clippings — and when you get to be my age you begin to wonder how much longer these things will be interesting to you.

At least this blog doesn’t take up too much physical space.

The early months of 2012 will undoubtedly see a continuation of this tedious, painstaking project. But I can say with assurance that there is a great deal less to be done than there was in October 2009. It’s conceivable that, next January, I’ll be celebrating a new year in earnest.Â