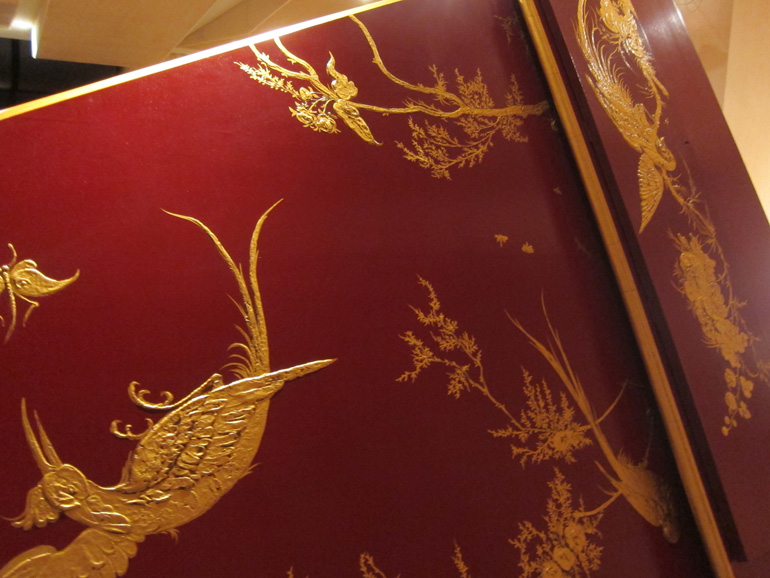

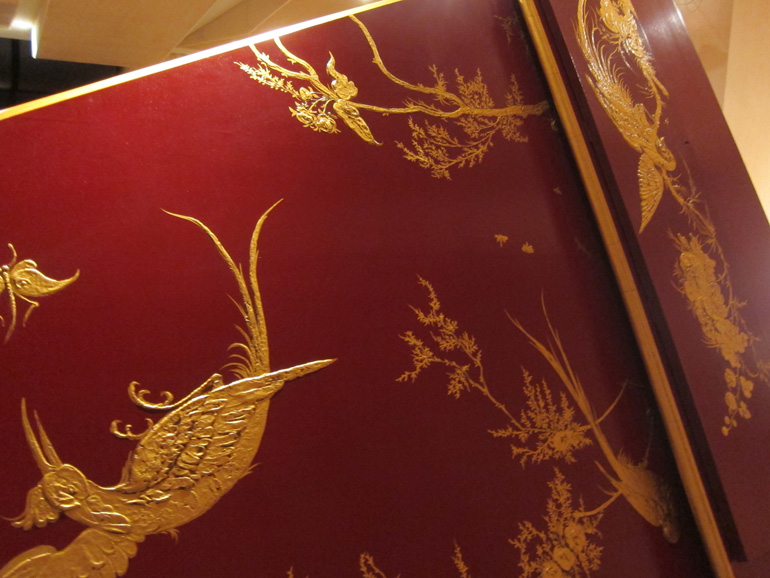

Sorry to be late today, and not to have any Commonplace offerings for the week. I do have a treat, though. Feast your eyes on this exquisite piano, a Pleyel made in 1890 (and yours, I’m told, for a mere $175,000) — an instrument that Proust might have seen and heard. You’ll have to take my word for it that the piano sounds at least as good as it looks; in fact, it sounded perfect, yesterday, at an informal lunchtime recital of French chansons (Ravel, Fauré, Debussy). Plans to make a recording of these beautiful songs, using this very piano, are in the offing, and I shall pass on the details as they emerge. For the moment, let the piano upstage the artists.

***

Why nothing for the Commonplace? Looking back over the week, I recall a lot of magazines, beginning on Sunday. Also, I read Jane Gardam’s 1985 novel, Crusoe’s Daughter — which has just been published by Europa. I’ve read four of Gardam’s novels now, Old Filth (“Filth,” by the way, is an acronym for “Failed in London: Try Hongkong”), The Queen of the Tambourine, God on the Rocks, and this new/old one. I have not read Faith Fox or The Man in the Wooden Hat, both of which I have here somewhere. Gardam is an interesting novelist partly because she still has very little presence in the United States; you will not be reading about her in the book reviews or in The New Yorker. You will not be reading her in The New Yorker; if there is still some sort of house style at that magazine, then Gardam still doesn’t fit it. Having read nothing but British fiction for well over six months now, I shocked by the first few pages of Crusoe’s Daughter; they’re so unlike what one would encounter at the beginning of Elizabeth Taylor or Tessa Hadley. After a while, I began to be aware that the novel was not just set in Yorkshire but set there, on the marshy coast of the “German Sea.” I remembered that the author was born in Yorkshire. And I thought of Shirley, Charlotte Brontë’s irregular but satisfying novel for adults. I haven’t been to Yorkshire myself, but it has a certain literary reputation as a place of some wildness. The wildness of Crusoe’s Daughter (Defoe’s hero hailed from Hull, also in Yorkshire) lies all in the writing. It is the beautiful wildness of a lithe, dangerous animal. There is nothing sad or defeating in Gardam’s heartbreaks. They are, on the contrary, truly awful.

Here shortly before World War I, Polly Flint, the title character, is brought by a family friend to his large estate near the banks of the Ouse. His sister, Lady Celia, is, we will learn, a fierce aesthete, playing the hostess to the likes of Virginia Woolf and detesting the local Jewish magnates not out of anti-Semitism but because they’re philistines. It is difficult to tell, in the following introduction, which is the bird of prey.

On a yellow silk sofa someone was lying. There was a blaze in the grate of a wood fire that never goes out, and there was also the smell of something else, very sweet. Pot-pourri — there was a heap of it in a great dish — but it wasn’t that. All I could make out on the sofa was drapery and a movement of white hands and a sense of eyes watching me.Â

“‘lo Celia. Back home. Polly. Polly Flint.” Mr Thwaite did the great harumming of the throat and moved to the window. There was a valedictory atmosphere about him. I have done what I have done. I have gone through with it. He looked at the sky. “Splendid day,” he said. “Very poor at Oversands. Continuous rain. Very disappointing.”

“Polly what?”

“Flint. Emma’s. Flint. Polly. Come for a little break.”

“Flint,” said the voice. “Well — Arthur. On your own? Arthur ring the bell. Polly Flint. Come over here.”

On the sofa lay a tiny woman dressed in silk. Pampas grasses in a tall jar bowed over her head like a regal awning. Her face was thickly painted — bright red mouth and cheeks. Her eyelids and brows were painted andher very black straight hair was pulled tight back across the skull like a Dutch doll, and looked painted, too. Her neck was not much thicker than a wrist and her ears glittering with round topazes were little and pretty like noisettes of lamb.Â

Her hands were very, very old and had veins standing on them but they were soft and unused, not as small as all that. Rather determined hands. She held one bravely out — it looked ready to drop with the weight of more topazes.

“But do come nearer.”

She examined my clothes one by one — hat to gaiters. She saw my pelisse, cut down from Aunt Frances’s and very special; I had worn it at the wedding. It was draped over my childish serge coat. She seemed to count the buttons down my calves and almost ate the big plate hat. She looked lower and I rememebered that there was an uncertainty about my left knicker elastic which I had meant to see to before I left.

“Thought of cinnamon scones,” said Mr Thwaite. “About tea-time?” We arrive upon our hour.”

“Polly Flint,” said (presumably) his sister. “How very interesting. How pretty Emma’s girl. Not at all like Emma. Very different — except perhaps for the cheek-bones. How very sensible of you Arthur. Has she come for a visit?”

Â